Rescue Dawn (2006) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | August 5, 2007

Christian Bale and the "Hollywoodized" version of Eugene DeBruin, as played by Jeremy Davies

Eugene DeBruin in reality, before his capture. He is still MIA

A Tale of Two Heroes

[xrr rating=4/5]

Rescue Dawn. Starring Christian Bale, Steve Zahn, Jeremy Davies, Marshall Bell, Zach Grenier, François Chau, Pat Healy, Teerawat Mulvilai, Yuttana Muenwaja, Chorn Solyda, Kriangsak Ming-olo, Abhijati ‘Meuk’ Jusakul, Lek Chaiyan Chunsuttiwat, and Andy Loftus. Music by Klaus Badelt. Art direction by Arin ‘Aoi’ Pinijvararak. Costume design by Annie Dunn. Cinematography by Peter Zeitlinger, B.V.K. Edited by Joe Bini. Written and directed by Werner Herzog. (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer/Gibraltar Films, 2006, Color, 126 minutes. MPAA Rating: PG-13).

Rescue Dawn is a great motion picture. German director Werner Herzog’s biopic is an inspiring film that recounts a daring POW camp escape during the early years of the Vietnam War. Recalling Steve McQueen’s role in Papillon, Rescue Dawn is a story about one man’s struggle against all odds—indeed, often against the inertia and fright of his own fellow prisoners—to break through to freedom.

It’s exactly the kind of audacious filmmaking you’d expect from Herzog, an equally audacious personality. In 1982, he directed the fantastical Fitzcarraldo, a sprawling epic about an obsessive hero: Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald (Klaus Kinski) longed to build an opera palace in the midst of the dense South American jungle, bringing legendary tenor Enrico Caruso there to perform. To realize his protagonist’s grandiose ambitions, Herzog staged what has got to be the cinema’s most spectacular scenes, beyond even Cecil B. DeMille’s wildest dreams. Hundreds of Indians moved a steamboat out of the river and onto land, bypassing dangerous rapids.

Thus did Fitzcarraldo’s impossible dream become Herzog’s own. One reason I’m so blasé about CGI special effects is from having seen this breathtaking sequence: No special effects or miniatures, but hundreds of extras breaking their backs, and the bizarre spectacle of a steamboat emerging through the clouds over a mountaintop summit.

A quarter-century later, Herzog returns us to the heart of darkness of the Laotian jungle in this equally excruciating work. Christian Bale gives a fervent, stirring performance as German-born U.S. Navy pilot Dieter Dengler. From early childhood, Dieter’s sole wish was to fly: As a small boy growing up in Nazi Germany during World War II, he experienced an epiphany as Allied pilots bombed and strafed his Bavarian village of Wildberg. Witnessing the attack in awe, he vowed to become a pilot when he grew up.

Shot down on one of his first missions over Laos in 1966, Dengler had to claw his way back to freedom, hacking through dense jungle vegetation, after many long months of imprisonment by Pathet Lao soldiers. Shortly after being taken captive and after suffering beatings, psychological torture, and starvation at the hands of his captors, he’s brought to the gemütlich office of a provincial governor (François Chau), who promises Dengler freedom if he signs a confession for committing “imperialist aggression.”

Dengler flatly refuses. “I love America,” the pilot explains, “America gave me wings. Will I sign it? Absolutely not.”

After being marched again through the blistering jungle heat, Dengler winds up in a prison run by sadistic youths with itchy trigger fingers. As soon as he’s locked up, he begins planning his escape from the poorly constructed bamboo hut. But, fellow captive Eugene (Jeremy Davies) nervously warns him: “This hut ain’t no prison. The jungle is the prison. Don’t you get it?” He advises waiting until monsoon season to make the grueling journey into Thailand, when it’s easier to drink fresh water and avoid dying of thirst.

Dengler’s fellow prisoners were imprisoned a couple years before he arrived, and during the months he plans their breakout, he often has to overcome low morale and backbiting, particularly from the squirrelly Gene, who would just as soon sabotage their plans than risk his life. Another fellow American prisoner, Duane Martin (Steve Zahn), has been weakened—both spiritually and physically—and as the men lie awake nights shackled, Dengler steadfastly tries to build up their hope and confidence. I admired Bale’s never-say-die performance: While his fellow cellmates spend a lot of time carping about the dangers of escaping, through his resourcefulness and optimism, Dengler helps rebuild the esprit de corps that had been beaten out of them. Despite torture and deprivation, what doesn’t kill Dengler makes him stronger.

The men share one wish: To get back home. Living on a handful ration of rice each day, they obsess about food, and fantasize aloud to each other about the contents of their refrigerators when they get back to civilization. To stress the isolation and hell of their internment, the men have tacked on the wall in lieu of pinup girls labels from canned beans, long since consumed, from a Red Cross parcel.

Rescue Dawn captures what it means to be an American. Through Dengler’s valorous feats of evasion and survival, Herzog brilliantly captures on film the astonishing true story of an individual who chose to become an American in the most meaningful way, and refused to back away from that choice, even under the most grueling of circumstances. Herzog also drives home the point of individual’s initiative triumphing over group inertia, which is a common thread running through literature and the arts since Ancient Greece. Rescue Dawn is a timeless tale of man’s triumph over men, and one of the few movies that portrays America’s actions in Vietnam in a positive, indeed laudable, light.

***

There’s just one problem with Rescue Dawn: In drawing Dengler’s character with broad, heroic, strokes director Herzog bent the truth. As with so many other movies “based on a true story,” Herzog condensed events and built up his protagonist’s accomplishments. Directors do this to create a more coherent narrative, and these instances of “résumé embellishment” do not bother me, because they don’t contradict the heroic essence of those remarkable individuals. For example, The Pursuit of Happyness buffed away some of the scuff marks of investor Chris Gardner’s rise. The World’s Fastest Indian had speed demon Burt Munro’s breaking the 200-mph barrier at Bonneville years before he actually did.

Likewise, Christian Bale’s authoritative performance honors Herzog’s longtime friend Dengler, who was awarded the Navy Cross and Distinguished Flying Cross for his unfaltering efforts. It is impossible for anyone with a conscience and a soul not to walk away from viewing Rescue Dawn without rightly being roused by Dengler’s story of courage and optimism.

And yet, I walked away from the theater with a sense that something was “off,” but I couldn’t put my finger on it. I received the answer in my inbox just as I sat down to write this review shortly thereafter in an e-mail forwarded to me by Erika and Hank Holzer, who are both actively involved with veterans’ causes. It’s link took me to a column posted on Debbie Schlussel’s blog, which made the case that Herzog built up Dieter Dengler’s character in Rescue Dawn by downplaying the character of fellow POW Gene DeBruin, portraying him as duplicitous and sociopathic.

Oddly, Herzog cast actor Jeremy Davies in the role of DeBruin. Schlussel noted that Davies previously played crazed mass murderer Charles Manson in the made-for-TV movie “Helter Skelter.” This observation jibed with my own notes: Upon first seeing Davies as DeBruin, I jotted, “looks like Charlie Manson.”

According to many who knew him, though, the real life Gene DeBruin was the opposite of the moral weakling and often treacherous “Eugene from Eugene, Oregon” onscreen version. “The portrayal was 180 degrees from who my brother was,” his brother Jerry DeBruin, a professor emeritus from the University of Toledo, told me in a telephone interview:

He wasn’t the kook portrayed onscreen. He was really even-keeled, and was the peacemaker when confrontation arose. He taught English to the Asian prisoners there, and shared his blanket with his fellow prisoners.

Indeed, even Dengler’s own account of DeBruin in his 1979 autobiographical book Escape From Laos, describes Gene DeBruin as inventive and gung-ho in plotting the escape. Far from being the cagey nut only concerned with his own survival, DeBruin, in fact stayed behind instead of escaping, to take care of an injured POW from Hong Kong, Y.O. Tou.

Why, then, would Herzog have chosen to portray Gene DeBruin so negatively?

***

In a 2006 interview, following the release of his documentary Grizzly Men, Herzog revealed his “ecstatic truth” philosophy of filmmaking:

“We have to start seeing and working and explaining and articulating reality movies in a different way. Cinéma vérité was the answer of the sixties. Today, there’s something else out there….Cinéma vérité is the accountant’s truth, as I keep saying—I’ve insulted many with that,” Herzog explained. “Facts do not create truth, they create norms.”

I wholeheartedly agree with Herzog’s thinking on this. If anything, his movies are not just entertaining, but ennobling. His heroes are heroic: bold, brave, and larger-than-life. More so than any living director, he grasps that the cinema is an inherently Romantic medium. One doesn’t so much view a Herzog movie as experience it. He interlaces his soundtracks with sublimely moving music from classical composers such as Wagner, Ginastera, Verdi, and Richard Strauss. It is this view of man and Earth that Herzog means by “ecstatic,” and—emotionally—this is what so resonates with me, and I would be lying if I said otherwise.

***

Yet, emotional identification with an artist’s aesthetic credo—even a director of the first order like Werner Herzog—cannot act as a substitute for intellectual honesty and judgment, and therein lies the rub. New Individualist Editor Robert Bidinotto registered his distate for the “docudrama” genre in his blog last September:

I have always disliked that weird hybrid of fact and fiction known as the “docudrama.” An inherently dishonest contrivance, it jumbles actual people’s words and deeds with fictional characters, invented dialogue, and imaginary occurrences—but never tells the audience which is which. […] The reputations of real people, living and dead, become toys for the docudramatist.

When interviewed by the New York Times shortly before the release of Rescue Dawn, reporter Mekado Murphy asked Herzog about “accusations” from DeBruin’s family that Herzog took “liberties […] with facts in Rescue Dawn.” Herzog’s reply echoed the 2006 interview:

If we are paying attention about facts, we end up as accountants. […] But we are into illumination for the sake of a deeper truth, for an ecstasy of truth, for something we can experience once in a while in great literature and great cinema. I’m imagining and staging and using my fantasies. […] Otherwise, if you’re purely after facts, please buy yourself the phone directory of Manhattan. It has four million times correct facts. But it doesn’t illuminate.

Unfortunately, Murphy’s interview with Herzog ends at this point. The answer almost comes off as a non-sequitur: It doesn’t address the seeming character attacks Rescue Dawn makes on Gene DeBruin’s character, or at best equates DeBruin’s depiction with factual trivia concerning the movie’s props.

I contacted Herzog with a number of pointed questions regarding the depiction of DeBruin vis-à-vis these comments. He responded both promptly and forthrightly. About that particular quote, he answered:

Dengler always understood that I was after the spirit of the story, its essence. […] In this context I spoke of the “accountant’s truth”, and in the specific interview you are mentioning I was pestered with questions coming at me many times why the film did show only six prisoners in the camp (seven is actually correct), why I did not show that Dengler was actually captured twice (again correct), why the film did not show that the prisoners were transferred from one camp into another (again correct), and so on, and I replied about Eugene DeBruin in this interview in a way I regret.

But, did Herzog actually defame Gene DeBruin’s character, through fabricated untruths, as alleged by Schlussel and Jerry DeBruin? In his e-mail to me, Herzog provides some factual context:

[I]n conversations with me, Dengler was quite often unhappy about his published book Escape From Laos, as it was cut down drastically by the publisher, and many human details got lost. Besides, Dengler always pointed out to me that the book was published fairly shortly after his rescue, and the search for Eugene DeBruin was still intense. He said to me at various occasions “this is the official version, but there are lots of things that should be told one day.”

Among those things were detailed accounts of tensions among the prisoners, and in particular conflicts with Eugene DeBruin. Dieter Dengler’s explanation was convincing: having spent years in medieval footblocks, having gone through starvation and disease, and having been subject to inhuman conditions, had worn down the men, or had led them into illusions about their imminent release. He said to me on many occasions that at some times “we would have strangled each other, had we not been handcuffed to each other.” Dengler had planned a feature film together with me long before he died, and he welcomed my detailed outlines of the feature film. I am certain he would have liked the result, Rescue Dawn.

Do I doubt Herzog’s explanations? Not for a moment. Here, we must again consider all the available evidence (which is often a luxury directors do not have within the time restraints of a movie). I certainly don’t advocate suppressing evidence, merely because it is not entirely charitable in portraying a person’s full character.

I am usually loath to use my reviews to make unsolicited editorial suggestions. I have no “frustrated screenwriter” inside of me, whose sole purpose is to nitpick and second-guess first-rate moviemakers. I do not think Herzog maliciously depicted Gene DeBruin.

Herzog wrote me that, “as a filmmaker I am not attempting to be a historian. There is a clear distinction between history and story for me. And second: it is in the nature of storytelling that you have to take one perspective, and mine is the perspective of Dieter Dengler.”

That said, I have to agree with Schussel’s assessment that so long as Herzog (self-admittedly) used a dramatic device which lopsidedly portrayed Gene DeBruin’s darker side, he ought to have created a composite, fictitious, character. That would have both honored Dengler, without doing damage to DeBruin’s reputation.

***

Rescue Dawn is a deeply engaging, though often deeply flawed, motion picture. It ought to be seen, because it’s clearly Werner Herzog’s labor of love in doing homage to the indomitable spirit of his friend, Dieter Dengler. That must be respected, and by no means do I want to suggest boycotting it.

Dieter Dengler passed away in 2001 from Lou Gehrig’s disease and was buried with full honors at Arlington National Cemetery. In Herzog’s prelude to this film, the 1998 documentary Little Dieter Needs to Fly, Dengler confessed, “I don’t think of myself as a hero. No, only dead people are heroes.” Here I must disagree with the otherwise self-assured Dengler—humility aside, he was truly heroic.

But, here’s something I do agree with Dengler on. In a videotaped interview, he quoted in awe his comrade Gene DeBruin, who made the painful decision to stay behind, rather than escape the hell of the POW camp, to take care of his friend Y.C. Tou, who was afflicted with malaria:

“I don’t care about that [staying behind], he’s my buddy, he’s my friend, and you guys go ahead, try to make it out.” […] He was really hard-core about that, there was just no way that he would waver. He said, “no, he’s my friend, we’ve been together in prison for two or three years, and if I have to die with him together, that’s what’s going to happen.”

Schlussel remarked about this poignant, pivotal, choice, “I think Gene DeBruin’s story is even more fantastic, not to detract from Dieter Dengler, who was genuinely heroic. But, to not take a chance at freedom in order to take care of a fellow prisoner—who was not even a American—is even more heroic.”

Herzog told me that he has just recently seen this testimony, and declared, “I find this very noble,” noting he now mentions it in all his recent public statements. “My hope is that Eugene DeBruin’s family will eventually come across more detailed documents about his fate,” he added.

The last time Jerry DeBruin and his family got news about his brother’s fate was in 1968, in which (in an unsubstantiated, though—as he describes it—from “very strong sources”) Gene was reported to have been re-captured by Pathet Lao forces after an attempted escape, and relocated to North Vietnam.

Jerry described his brother to me thusly,

Gene sacrificed freedom to save his friend Tou, who although he has balls the size of oranges, could not walk. This is who my brother was. He was my mentor, and a very caring individual….We continue to search for this very day. The mission, is if he’s alive, is to return. If he’s dead, to be returned to us for proper burial of his remains. This September fifth will be the forty-fifth year of our mission. We won’t give up searching for him.

I cannot but respectfully disagree with Werner Herzog in how he chose to illuminate Dieter Dengler’s heroism in making Rescue Dawn. I do not believe Dengler’s story can be told without telling Eugene DeBruin’s full story. Not just the warts, but also in rightly paying tribute to DeBruin’s own acts of gallantry.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New YorkPost, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

· To get a fuller picture of Eugene DeBruin’s character and legacy, visit his brother Jerry’s website at www.rescuedawnthetruth.com

Topics: Action Movies, Biopics, Docudramas, Dramas, Independent Films, Movie Reviews, War Movies |

Ace in the Hole (1951) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | July 25, 2007

Wilder Than Reality Television

[xrr rating=5/5]

Ace in the Hole. Starring Kirk Douglas, Jan Sterling, Bob Arthur, Porter Hall, Frank Cady, Richard Benedict, Ray Teal, Lewis Martin, John Berkes, Frances Dominguez, Gene Evans, and Frank Jaquet. Music by Hugo Friedhofer. Cinematography by Charles B. Lang, Jr., A.S.C. Edited by Arthur Schmidt; Editorial supervision, Doane Harrison. Screenplay by Billy Wilder, Walter Newman, and Lesser Samuels. Directed by Billy Wilder. (Paramount, 1951, Black and White, 111 minutes. MPAA Rating: Not Rated.)

The legendary Billy Wilder is my all-time favorite director. Many friends and those who read my reviews wrongly assume that Alfred Hitchcock is, and that’s understandable. No other director, before or since Hitch, has had as intuitive a grasp of film as a visual medium, of how to use not only the camera but also editing to tell a story.

However, as much as I admire Hitchcock’s classic thrillers, no director has inspired awe in me as much as Wilder. One of his enduring creations, aging screen siren Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) in Sunset Blvd., voiced words that, coincidentally, explain what made Wilder’s movies so memorable:

There was a time in this business when they had the eyes of the whole wide world! But that wasn’t good enough for them, oh no! They had to have the ears of the world, too! So they opened their big mouths and out came talk. Talk! Talk!

And what talk! For the Austrian-born Jewish émigré, who fled Europe in the early 1930s when Hitler rose to power, the slang he picked up after he arrived on our shores was frenetic jazz music to his ears. It didn’t take him long to channel his love of American lingo into feisty dialogue for comedic screenplays that he crafted with co-writer Charles Brackett. An urbane New Yorker, Brackett sanded the rough edges off Wilder’s somewhat broken English. Their one-two punch of pugnacious palaver for such movies as Ernst Lubitsch’s Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife and Ninotchka made them a hugely popular screenwriting team.

Take Howard Hawks’s 1941 Ball of Fire. Barbara Stanwyck plays a wisecracking burlesque dancer. When fussy linguistics professor Gary Cooper examines her throat and gives his diagnosis, Stanwyck shoots back: “A slight rosiness? It’s as red as the Daily Worker and just as sore!” It’s typical Wilder dialogue: sharp, silly, and stylized.

Just as Hitch was the “Master of Suspense,” Wilder was the master of farce. Think of Tony Curtis donning yachting clothes and deadpanning a hilarious Cary Grant impression in order to win Marilyn Monroe in Some Like It Hot. Or Jack Lemmon humming Tchaikovsky’s Capriccio Italien off-key and straining spaghetti through a tennis racket for Shirley MacLaine’s dinner in The Apartment. But Wilder’s genius was not limited to comedy: his dramas were among the best ever filmed.

Though he wrote for first-rate directors like Hawks and Lubitsch (whose elegant, lighthearted touch he later emulated), the fiercely independent Wilder decided to strike out on his own and direct when Mitchell Leisen butchered his and Brackett’s screenplay for Hold Back the Dawn. Wilder turned out a pair of well-received movies for Paramount—the Ginger Rogers comedy The Major and the Minor and the World War II thriller Five Graves to Cairo. But it was his 1944 adaptation of James M. Cain’s controversial pulp novel Double Indemnity that propelled him into the first rank of directors.

For that classic, Wilder audaciously broke every rule of movie storytelling. He cast nice guy Fred MacMurray as the heavy and made perennial gangster Edward G. Robinson the movie’s moral center. Then he gave away the ending in the opening narration, as sap MacMurray, bleeding to death and slipping into unconsciousness, confesses into a Dictaphone: “Yes, I killed him. I killed him for money—and a woman. I didn’t get the money and I didn’t get the woman.”

That daring paid off, big. Audiences were riveted to their seats as femme fatale Barbara Stanwyck lured the hapless insurance man to his doom. In 107 minutes, Wilder (working with hardboiled crime novelist Raymond Chandler) created a new movie genre: what French movie critics would later call film noir.

Although Double Indemnity would become the template for hundreds of crime movies through the late 1950s, Wilder never again made an outright noir. Instead, he incorporated many of its elements—voiceover narration, close-ups combined with dissolves, and a dark, cynical view of human nature—into gripping melodramas likeThe Lost Weekend (for which he won the best director Oscar in 1945) and Oscar-winning comedies like Sunset Blvd. and Stalag 17.

After he and Brackett won the best original screenplay Oscar in 1950 for Sunset Blvd. (their last collaboration), Wilder embarked on an ambitious project: He would write, direct, and also produce a film. For the 1951 Paramount project, he brought in radio dramatist Walter Newman as his collaborator and playwright Lesser Samuels to polish the dialogue. He also cast in the starring role a young Kirk Douglas, fresh off his volatile performance in Champion. The result was Wilder’s ruthlessly dark yet larger-than-life masterpiece: Ace in the Hole.

For more than a half-century, Ace in the Hole has languished in Paramount’s vaults. But it finally has been released by Criterion Collection, in a pristine transfer to DVD. The story behind this forgotten classic’s fate is as intriguing as—well, as a Billy Wilder movie.

But first, the tale itself.

Douglas plays Chuck Tatum, a sensationalistic New York newspaperman down and out in Albuquerque, New Mexico. His car’s got bad brakes and a busted wheel bearing. His reputation’s in need of even greater repair as he ambles arrogantly into the publisher’s office of the small-time Sun-Bulletin, trying to land a job. “I’ve been fired from eleven papers with a total circulation of seven million,” Tatum brags to editor Jacob Boot (Porter Hall). “I can handle big news and little news. And if there’s no news, I’ll go out and bite a dog.”

Boot’s a no-nonsense straight arrow, over whose desk hangs the paper’s motto, immortalized in cross-stitch: “TELL THE TRUTH.” Warily, he hires Tatum. For his part, Tatum aims to get a scoop in a week or two—a big story that the wire services will pick up and that will land him back on a big East Coast paper.

After a fade-out, the story resumes a year later. Tatum’s still stuck in the “sunbaked Siberia,” covering mundane stories about county fairs and grip-’n’-grin ceremonies. He and young photographer Herbie (Bob Arthur), who idolizes him, are dispatched into the countryside to cover a rattlesnake hunt. On the drive, Tatum knocks Herbie’s journalism school education and touts his own cynical philosophy: “Bad news sells best—because good news is no news.”

But just as the film seems to be only a new spin on The Front Page—set to Hugo Friedhofer’s jaunty, Gershwinesque score—it takes a sudden, dark turn. The pair stops to fill up their tank in the tiny hamlet of Escudero and learn that a man is trapped underground in a pueblo cliff dwelling, where he was searching for Indian relics.

Despite a cop’s objections, Tatum bullies his way into the cave with Herbie tagging along. Excited, he recalls the (real-life) Kentucky cave-in that trapped explorer Floyd Collins in 1925 and tells Herbie, “A reporter on the Louisville Herald crawled in for the story—and came out with a Pulitzer Prize!”

They find Leo Minosa (Richard Benedict) pinned beneath fallen boulders. Tatum snaps his photograph and tries to build up his confidence, telling him help is on the way. Emerging, he sets up his typewriter in the general store and pounds out a tall tale about how luckless Leo was trapped underground by vengeful spirits of the Indian dead.

The next morning, though, a local construction contractor (Frank Jaquet) estimates his crew can shore up the walls and quickly get Leo out. Tatum suddenly sees his Pulitzer slipping out of reach—and it’s too much.

Muscling his way across the screen, Douglas delivers a frightening, sinister performance. He promises the corrupt local sheriff (Ray Teal) that he’ll use his byline to get the man re-elected—if, in exchange, the lawman will pressure the contractor to change his rescue strategy. Instead of shoring up the cave, they’ll rescue Leo by setting up a drilling rig on the top of the mountain—a delay that will give Tatum a week to milk the story.

Jan Sterling plays Leo’s bottle-blonde wife, Lorraine, a tramp trapped in a lousy marriage. She married Leo for the same reasons as any other gold-digger, but resents that she only struck dirt, while her naïve husband worships the dirt she walks on. Tatum has snowed Leo’s parents into thinking he’s their son’s savior, but Lorraine is wise to his deception. “Yesterday, you never heard of Leo. Today you can’t know enough about him,” she smirks. “Aren’t you sweet.” As she prepares to blow town, Tatum reproaches her for abandoning her husband beneath the fallen rocks. “Honey,” she shoots back, “you like those rocks just as much as I do.”

Wilder uses a lot of symbolism from the book of Genesis to depict these scoundrels: Lorraine, the story’s Eve, slyly bites into an apple; Sheriff Kretzer, a serpent of a public servant, keeps a pet rattlesnake in a shoebox; and meanwhile, Tatum plays God for the seven days of Leo’s usable media life.

Chuck Tatum’s an Elmer Gantry—a smooth-talking charlatan who inveigles his way out of anything and everyone out of his way. But there’d be no Gantrys without the Babbitts who fall for their hokum. As Tatum’s copy gains traction with the public, curiosity seekers move on Escudero by the dozens, then thousands, hoping to make their own lives more important through their proximity to tragedy. The land outside the cliff dwelling is transformed into a literal media circus as a carnival erects a Ferris wheel. “We’re coming, we’re coming, Leo!” croons a country singer while a woman hawks sheet music of the song (a biting reference to country-western singer Vernon Dalhart’s exploitive 1925 song “The Death of Floyd Collins”).

When no one’s looking, Tatum silently grieves for Leo, although he keeps things in “proper perspective”—the story comes first, and a lone man’s race against time is how the story plays best. But the mob is Wilder’s real villain: They set up camp tents, shill cotton candy, and ride the tilt-o-whirl; for the rabble, it’s all just entertainment.

Wilder never lets up the tension, either. The narrative and Friedhofer’s orchestrations (now full of thundering timpani and Richard Straussian chromatics) pound ceaselessly, like the drill smashing through the rock, inching ever closer to Leo. The movie’s bravura finale sent a lightning-quick chill straight up my spine.

As social commentary, Ace in the Hole was years ahead of its time, foreshadowing such cautionary films as Elia Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd and Sidney Lumet’s Network. It flopped when first released, so badly that the studio pulled it from circulation and re-released it with the title The Big Carnival. Critics in the print media savaged it because Wilder had the chutzpah to attack their bread-and-butter methods so pitilessly. As a result, Paramount so neglected the movie that it’s rarely shown even on television and, until now, has never been released in any home-video format.

In an interview, Wilder called this tale “sanitized” compared to his experiences as a young writer for a scandal sheet in Vienna, when the paper sent him to interview the parents of murderers and their victims and to ask the universally reviled question, “How do you feel?”

The film was not successful because I brought the audience into the theater expecting a cocktail and instead I served them a shot of vinegar. . . . People rebelled against this image of themselves. Yet, when there is a plane wreck at Kennedy Airport the freeways are clogged with automobiles of people wanting to see the carnage. Meanwhile someone is going around selling weenies and spun sugar.

Has anything changed? If you want to see human depravity and mob psychology at its worst, just tune in to the 24/7 electronic media and witness their coverage of whatever disaster du jour is dominating the headlines. You’ll see that the circus is still going strong.

Ace in the Hole is not easy to watch. It’s not supposed to be. Kirk Douglas’s commanding performance as Chuck Tatum had me flinching, squirming. Billy Wilder didn’t live long enough to see this movie earn its rightful place alongside so many of his great classics, but he always knew its worth. “For a long time, when people asked, ‘Which is your favorite film?’ I answered, ‘Ace in the Hole.’ I like that picture. I am proud of it.”

As a man of integrity and independence, he had every right to be.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Black Comedies, Classic Movies, Comedies, Melodramas, Movie Reviews, Restored Re-releases |

Live Free Or Die Hard (2007) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | June 27, 2007

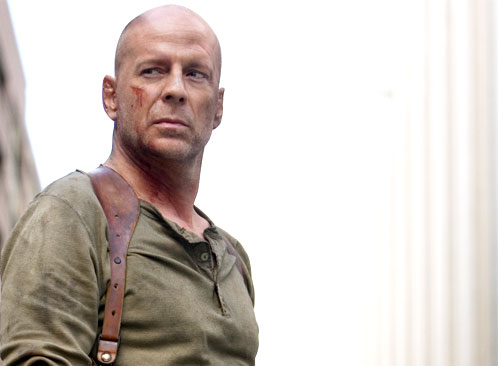

John McClane's finally lost all his hair, but he's still got his million mile stare

He Takes a Licking but Keeps on Ticking

[xrr rating=4/5]

Live Free or Die Hard. Starring Bruce Willis, Timothy Olyphant, Justin Long, Maggie Q, Cliff Curtis, Jonathan Sadowski, Andrew Friedman, Kevin Smith, Yorgo Constantine, Cyril Raffaelli, Chris Palermo, and Mary Elizabeth Winstead. Music by Marco Beltrami. Cinematography by Simon Duggan, A.C.S. Production design by Patrick Tatopoulos. Costume design by Denise Wingate. Edited by Nicholas DeToth. Screenplay by Mark Bomback. Story by Mark Bomback and David Marconi. Article “A Farewell to Arms” by John Carlin. Certain original characters by Roderick Thorp. Directed by Len Wiseman. (20th Century Fox, 2007, Color, 130 minutes. MPAA Rating: PG-13.)

It’s hard to believe that Bruce Willis’s wisecracking NYPD detective John McClane has been absent from the big screen for a dozen years. With this blistering fourth installment of the Die Hard series, Willis seems to be laying claim to the “last man standing” title in the action movie genre. Which is appropriate, because almost twenty years ago, Willis and director John McTiernan (who returns as producer on this one) practically invented the smartass tough-guy action flick with their spectacular Die Hard, a film that promised—and delivered—“Forty stories of sheer adventure!”

In the original, ruthless villain Hans Gruber (played by a suave, menacing Alan Rickman) and his Eurotrash henchmen took over and terrorized an L.A. high-rise to loot the Nakatomi Corporation’s heavily guarded vaults. Like clockwork, everything went according to plan—except for one thing they didn’t plan on: Hard-boiled New York police sergeant John McClane was in the building. McClane was visiting the City of Angels on Christmas Eve to salvage his marriage to wife Holly (Bonnie Bedelia), who had accepted an executive position on the West Coast to advance in the corporate world. When the goons started taking hostages, McClane started taking back the building, playing a bloody game of cat-and-mouse with Gruber and his gang.

What made Die Hard an unexpected smash hit was McClane’s sheer style. The sardonic cop hunted down the criminals and picked them off one by one, tossing off sarcastic one-liners and four-letter words while laying waste to the building. Audiences thrilled to this rollercoaster ride of a movie, not only for its spectacular action scenes, but also because it didn’t star a muscle-bound hero like Stallone or Schwarzenegger. Willis’s McClane was a regular working stiff, a guy who made up for his lack of brawn with quick-witted common sense and uncommon resourcefulness, persevering when all options for survival seemed exhausted.

As he raced against the clock to rescue the skyscraper’s occupants, the no-nonsense McClane didn’t have time to go by the book. Half his battles were against LAPD and federal bureaucrats who did little except to dither and throw procedural roadblocks in his path. His combination of decisive action and impudence resurrected a distinctively American hero type—a throwback to Humphrey Bogart’s wisecracking detective Sam Spade from The Maltese Falcon and Clint Eastwood’s supremely insubordinate San Francisco cop, “Dirty Harry” Callahan. By movie’s end, McClane had destroyed half the Nakatomi Tower, killed all the bad guys, saved the day, and won back the girl. What more could we have asked for?

Die Hard’s premise—“the wrong guy in the wrong place at the wrong time”—has been copied numerous times since, in such movies as Speed and Passenger 57. It’s become so formulaic, in fact, that when the third installment in the franchise, Die Hard: With a Vengeance, was released in 1995, the pairing of Willis with Samuel L. Jackson came off more like Lethal Weapon 3-1/2 than a sequel. The fine line between action and comedy, navigated so deftly in the first two films, veered too much into silliness in the third, with the racial-tension subplot between the two leads undermining whatever suspense the movie aspired to build. That, plus Jeremy Irons’s hammy performance as Hans Gruber’s vindictive brother Simon, made for an anticlimactic motion picture.

Thankfully, with Live Free or Die Hard, director Len Wiseman delivers a genuine edge-of-your-seat action movie of the kind that’s been missing from the big screen since Willis still had a head full of hair.

This go-around, John McClane is back and badder than ever. He’s still a formidable S.O.B., still serving On The Job in New York, still barely staying on the wagon, still divorced, and still estranged from the kids. That estrangement doesn’t stop him from tailing daughter Lucy (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) at her Rutgers campus in the dead of night and forcibly removing her boyfriend from her parked car when the fellow gropes too far below her neckline. (Not that McClane really needed to—Lucy’s tough enough to enforce her own borders, you see.)

He gets a call to drive down to nearby Camden and serve a warrant on suspected computer hacker Matt Farrell (Justin Long) and bring him to FBI headquarters in Washington. Just as he’s about to pick up his man, McClane gets pinned down in a hail of machine-gun fire from unknown assassins and barely manages to extricate Farrell.

So the action begins. And the action doesn’t let up for almost two solid hours. By the time the two get to D.C., we learn that Matt is one of eight hackers who had been recruited to write code for a mysterious employer with (unbeknownst to them) nefarious aims. Once they served their purpose, every one was slain—except Farrell.

As the sun rises, it’s the Fourth of July—and all hell breaks loose. The nation’s transportation infrastructure goes haywire as all traffic signals turn green, causing cars, trucks, buses, and trains to collide. When McClane arrives to transfer his prisoner to FBI computer-security agents, he realizes that Farrell is the only one who grasps the method behind the madness grinding every metropolitan area to a standstill.

“It’s a fire sale,” Farrell explains to McClane and FBI agent Bowman (Cliff Curtis). “Everything must go.” He means an Information Age equivalent of 9/11, with cyberterrorists taking over government computer networks and crippling America’s transportation, financial, and public-utility infrastructures.

In time, the pair discovers that the meltdown is the megalomaniacal revenge plot of übergeek Thomas Gabriel (Timothy Olyphant), who used to occupy a spot high up the Department of Defense food chain. For years, Gabriel had warned DoD officials that America’s computer-network security was vulnerable. To prove his point, he had used a laptop to shut down NORAD. Rather than being given a commendation for his efforts, though, Gabriel got the pink slip.

Left to his own devices, technological dinosaur McClane wouldn’t have had the savvy even to begin to hunt down the elusive Gabriel. And left to his own devices, wan hacker Farrell probably couldn’t have beaten one of his own collectible action figures in a fair fight. But, thanks to the division of labor and the time-tested sidekick plot device, this temperamentally mismatched team is unstoppable.

Charging through a rapid-fire series of action scenes, McClane is a human battering ram, taking out the bad guys and giving techno-wizard Farrell time to hack into the system and try to undo the damage. What a stroke of casting genius to pair the cantankerous McClane with the Mac Guy from Apple’s TV commercials, in order to figure out the cyber pirates’ next moves and head them off at the pass!

This is a nearly perfect action picture, and just in time, too: I thought they forgot how to make ’em like this. For a movie so preoccupied with computer Armageddon, it eschews over-reliance on CGI special effects, opting instead for a stylized, yet gritty, look that never overwhelms the real with the virtual. Simon Duggan’s adroit camerawork and Nicholas De Toth’s editing hit all the marks, reasserting the brutal aesthetic of the original as the visual standard for action films.

Like Bruce Willis’s forthright portrayal of John McClane, Live Free or Die Hard is refreshingly Old School. McClane is a situational hero, not the mythological “One.” There are no Matrix-style shots of him plinking bullets out of mid-air as he suspends time through Zen-like mental focus. In many ways, this is the anti-Matrix. When Asian siren Mai Linh (Maggie Q) puts her kung fu moves on McClane, the camera doesn’t pan 360° as the two fighters go into Praying Mantis poses. Our hero just dusts himself off, gets behind the wheel of a Ford Explorer, revs it up, and slams her across the room and down an elevator shaft.

Shortly after he launches a police squad car airborne in order to take out a helicopter, he and Farrell find themselves back on the road. Still shaken after being fired upon by Gabriel’s henchmen, Farrell asks the seemingly detached cop what it’s like being “a hero.”

“You know what you get for being a hero?” McClane fires back. “Nothing. You get shot at. Get divorced. Eat a lot of meals alone. Your kids won’t talk to you. Nobody wants to be that guy.”

“Then why do you do it?”

“Because there’s nobody else to do it, that’s why,” he replies.

That’s a real man’s answer. Only a naïve boy would set out to do heroic deeds; a man has the wisdom to know that true heroism is revealed when trying circumstances put character to the test. To a cop, being a hero means more than just showing up for work; it means seeing the job through. In the tradition of the best action heroes, John McClane does the dirty work most people can’t or won’t do.

Like last year’s Rocky Balboa, Live Free or Die Hard bookends admirably with its original. More than the previous two sequels, it captures the timeless spirit of the lone “cowboy” with a score to settle.

At one point, Gabriel smugly mocks McClane: “You’re a Timex watch in a digital age.” But when he takes McClane’s daughter Lucy hostage, he learns the hard way that McClane is also a ticking bomb.

Millions of fans can only say: Yippie ki-yay!

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Action Movies, Comedies, Movie Reviews, Sequels, Suspense Movies |

The Page Turner (2006) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | April 6, 2007

It's like... like she's studying you, like you was a play or a book or a set of blueprints: How you walk, talk, eat, think, sleep

Rondo Vizioso più Agitato

[xrr rating=4/5]

The Page Turner (La Tourneuse de Pages). Starring Catherine Frot, Déborah François, Pascal Greggory, Xavier de Guillebon, Christine Citti, Clotilde Mollet, Jacques Bonnaffé, Antoine Martynciow, Julie Richalet, Martine Chevallier, André Marcon, and Arièle Butaux. Music by Jérôme Lemmonier. Cinematography by Jérôme Peyrebrune. Editor-in-Chief, François Gédigier. Written by Denis Dercourt and Jacques Sotty. Directed by Denis Dercourt. (Tartan Films/Diaphana Films, 2006, Color, 85 minutes, in French with subtitles. MPAA Rating: Not Rated).

Thanks to the people of France—who’ve finally come to their senses and reversed the course of national suicide on which they were careening, by electing Nicholas Sarkozy as their president—I can now avail myself of fine products of that nation, which I had hitherto been boycotting. I am now free to gorge on toasted Camembert and wash it down with my favorite Bordeaux wine, Mouton Cadet Rosé (I know, I know–Rosé!–how gauche of me). My little boy Evan can now laugh at the looney shenanigans of Pepe Le Peu. More significantly, I am able to once again treat myself to Gaul’s outstanding film exports.

Just in time, too: Writer and director Denis Dercourt’s The Page Turner is quite a brilliant gem of filmmaking. I first approached watching it with trepidation, because the poster touted a suspense movie in the tradition of Alfred Hitchcock and Claude Chabrol. Usually such laudatory advertising hype bears little relation to what’s actually on the screen, by semi-competent directors whose pictures usually bear only superficial resemblance to these masters of suspense, but with only the most vague understanding of what makes a movie suspenseful. Fortunately, such is not the case here: The Page Turner is a brilliantly paced psychological flick that recalls Hitchcock’s Marnie, but more so than Chabrol, it reminded me of François Truffaut’s revenge thriller The Bride Wore Black.

Déborah François, in just her second leading role (her excellent debut was in The Child in 2005), is icily persuasive as Mélanie Prouvost, an alluring and duplicitous femme fatale. As the credits dissolve, we find her a young girl of eleven, practicing the piano in hopes of winning a coveted scholarship to a musical conservatory. She lives in a comfortable bourgeois flat above her parents’ butcher shop. Her audition, however, is rudely interrupted when a classical music fan rudely asks jury member, famed pianist Ariane Fouchécourt (Catherine Frot), for an autograph. Unable to pick up where she left off, Mélanie fumbles her way through the rest of the piece. Fuming as she leaves the audition, she goes home and stows away the bust of Beethoven that graced her family’s upright piano, presumably forever.

We next see Mélanie as an attractive young lady, working as a filing clerk at a Paris law firm. Although of demure demeanor, she nonetheless projects an intense determination in her hard-set eyes. She quickly obtains a position from her boss (Pascal Greggory) as nanny for his son, at his country estate. Soon, we learn the reason why: M. Fouchécourt’s wife is the musician whose insensitive autograph signing crushed the younger Mélanie’s hopes of embarking on a career as a concert pianist a decade before.

In short order, Mélanie insinuates herself into the family’s daily life, as she goes outside of her job description to help their son Tristan (Antoine Martynciow) with his piano studies, and by becoming Ariane’s assistant. Instead of the arrogant virtuoso of ten years before, Mélanie finds Ariane shaken by an automobile accident, and humbled by a case of nerves and stage fright. As if on cue, Mélanie volunteers her services as Ariane’s page-turner. Because of her pianistic knowledge, she proves herself an adept and sensitive collaborator during rehearsals of the trio to which Ariane belongs, and immediately wins the older woman’s trust and friendship.

Methodically, Mélanie exploits the situation through a series of connivances that places Ariane in a desperate state of dependence upon her charge. She’s as calculating as Anne Baxter in her defining role in All About Eve, but, strangely, Mélanie is so cold that she’s oblivious to the bounties of fame and fortune; her sights are set solely on Ariane’s demise.

Photography director Jérôme Peyrebrune’s shots are almost all static, objective; this tale of deceit is told almost entirely through editor François Gédigier’s exactingly tight montage. The tension is further notched up through composer Jérôme Lemmonier’s minimalist score for strings, which underscores Mélanie’s monomaniacal obsession. The use of Schubert’s “Notturno” trio and Shostakovich’s agitated Second Piano Trio are brilliant counterpoint in foreshadowing her evil intentions: Ariane, her violinist and ‘cellist are oblivious to Mélanie’s ploy, but through juxtaposing the young protégé’s fixed stare with the slashing strings and percussive piano beat, director Dercourt skillfully evinces her ruthless cruelty.

By the end of the film, through an intricate series of twists and turns, Mélanie has wreaked lasting destruction on the entire Fouchécourt family. Although there are many striking parallels between François’s character and Rebecca De Mornay’s chilling performance in The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, the revenge Mélanie exacts is of a bloodless variety. Superficially, it’s appropriate payback since the only murder being avenged is the death of Mélanie’s childhood dreams at the negligent hands of Ariane.

I found both François’s portrayal of Mélanie and her visual depiction quite unsettling: When she is shown outside the context of her plot against Ariane, Mélanie’s life is pitifully empty, her lonesome existence preoccupied with quotidian household tasks and perfunctory phone calls to her parents. After her dirty work is done, she is seen walking along an empty farm road to the train station. But, her face is still an emotional cipher—she exudes neither elation nor guilt. Life goes on, but to what sort of life will Mélanie return?

Usually, a revenge tale is meant to instill cathartic emotions, either for the hero who has undone a great evil (such as Charles Bronson in Death Wish) or against a villain who’s gone too far (think Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction). Yet, Dercourt does not let Mélanie off so easily: there is no catharsis offered here—only stasis.

Certainly, we will never be privy (unless there’s a sequel, which is unlikely) to the trebling effects of the pain suffered by Ariane and her family. But, we have witnessed a young girl shoulder a grudge for half her brief life that any sane person would have gotten over in a few months, perhaps a year, and gone back to the drawing board.

Subtly, Dercourt’s visual narrative turns the tables on its antagonist without her even being aware. By dedicating her life to righting a largely imagined wrong, Mélanie permanently and irrevocably has robbed herself of any semblance of a productive and fruitful life. Disturbingly, The Page Turner demonstrates how placing one’s self-esteem at the mercy of others sabotages any hopes of actually attaining self-esteem. The pages Mélanie turns are only those in a piano score, but fates herself to never turning over a new page in her own life’s book.

The Page Turner is an instance of a film that truly invokes thought long after the audience has left the theater, and is the most tantalizing suspense movie I’ve seen since David Mamet’s The Spanish Prisoner. Its particular genius is that in an age when most directors today will try to overwhelm viewers with C.G.I. special effects and obvious cinematic pyrotechnics, Denis Dercourt is able to send a shiver right through the viewer through the forgotten art of dramatic understatement and virtuosic montage.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Dramas, Foreign Films, Independent Films, Movie Reviews, Suspense Movies |

Offside (2006) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | March 29, 2007

Evil transgressor cross-dressing women thrill to a soccer match they aren't permitted to watch in Jafar Panahi's "Offside"

Waiting for Gomorrah

[xrr rating=4/5]

Offside. Starring Sima Mobarak-Shahi, Shaesteh Irani, Ayda Sadeqi, Golnaz Farmani, Mahnaz Zabihi, Nazanin Sediq-zadeh, Melika Shafahi, Safdar Samandar, Mohammad Kheir-abadi, Masoud Kheymeh-kabood, Mohammed-Reza Gharebaghi, Hadi Saeedi, Masoud Gheyas-vand, Ali Baradari, and Ali Roshan. Music by Yuval Barazani and Korosh Bozorgpour. Cinematography by Rami Agami and Mahmoud Kalari. Production design by Iraj Raminfar. Screenplay by Jafar Panahi and Shadmehr Rastin. Edited and directed by Jafar Panahi. (Sony Pictures Classics/Jafar Panahi Film Productions, 2007, color, 93 minutes, in Persian/Farsi with subtitles. MPAA rating: PG.)

“Men and women are different,” says a frustrated soldier to a young girl who’s been questioning his authority in Jafar Panahi’s lighthearted journey into fear, Offside.

No kidding. It’s why men are into Dodge Challengers painted Hemi Orange while women are enrolled in Oprah’s Book Club. The last time I attended a Redskins game, at Philadelphia’s now-demolished Veterans Stadium, I went with a young lady who just happened to be an Eagles fan. And, although you might call her a tomboy (she does), when she was finished swilling her Yuengling beer, she had to use the ladies’ room. Because, after all, men and women are different.

In Tehran’s Azadi Stadium, however, there are no women’s restrooms. That’s because no women are admitted anywhere in the stadium; only men are permitted to attend the sporting events. Because of the repressive separation of the sexes in the Islamic Republic of Iran, women wind up paying the price for men’s rude behavior and lechery.

The inspiration for this film, shot in “real time” documentary style, first germinated in director Panahi’s mind a few years before it was shot, when he had an assignment of covering a soccer game. His preteen daughter begged to tag along, but he told her she wasn’t permitted. Because he couldn’t miss the game, he informed her that should she be turned away at the gate, she’d have to return home alone. Though Panahi was unsuccessful at getting her in, she later told him that she managed to slip through. When he asked how, she replied slyly, “There is always a way.”

This movie’s plot is rather simple: Adolescent girls disguise themselves (with varying degrees of success) as boys, in hopes of watching the Iranian national soccer team face off against Bahrain in a qualifying match that will send the winner to the 2006 World Cup in Germany. Although some gatecrashers slip by undetected, a half-dozen are caught by army soldiers and detained.

Throughout this cinematic slice of life, when the girls are caught sneaking in, they are lectured by men that they shouldn’t be around the male soccer fans, who might be acting loutish and shouting profanities, which could deflower the girls’ virginal ears. One poorly-disguised young fan (Sima Mobarak-Shahi)—whose features are far too soft and feminine to be taken for a boy—offers a souvenir dealer (Mohsen Tabandeh) 6,000 rials for a ticket. He retorts, aghast, “But you could be my sister!” When the girl offers him more, they strike a deal: Apparently, the going rate for the honor of the ticket scalper’s sister would be 8,000 rials.

Almost immediately she is apprehended by a soldier, who leads her over to a makeshift holding pen outside the stadium’s walls. There she is held with five other girls. As they sit, stand, pace, and gripe behind the fence barricades, they cajole the soldiers to let them go, to no avail.

But not necessarily because their guards are unsympathetic to their plight. The movie’s paradox is that while the girls long to be on the inside, the soldiers would all rather be elsewhere. These captors are also captives, by way of conscription. Their dedication to duty comes not from love of country, but from the dread that their enlistments might be involuntarily extended should one of the girls slip from their grasp. One troop even gives a play-by-play rundown to the girls through an opening in the stadium’s wall while he watches the action on the field. Panahi lets the viewer revel in the game from the same point-of-view as the girls’, by proxy.

Panahi’s portrayal of fundamentalist Islam’s oppression of its women is hardly oppressive; rather, he depicts their plight as a bureaucratic nightmare. Everyday life is absurdist theatre in today’s Iran, where women cheer on their national soccer heroes at a game they cannot see. For them, breaching the stadium’s walls is as vital as scaling the Berlin Wall was for East German dissidents a generation before. Ironically, though, these girls were brought here not by a spirit of rebellion against the Iranian regime, but out of patriotism, in hopes of witnessing their countrymen advance to the World Cup. Instead of land mines and electrified fences, they face stadium walls that have been thrown up by a dualistic philosophy that views women as simultaneously pure yet the source of temptation. Its practical result is the hypocrisy that women are to blame for men’s uncontrollable lusts; thus, even the most commonplace, non-carnal pleasures cannot be shared with their male counterparts.

A particularly amusing scene involves a soldier (Safdar Samandar) faced with the quandary of having to escort his female prisoner (Ayda Sadeqi) to the men’s room to relieve herself. He cannot permit her entry because of her sex, so before she can enter, he rounds up the young men and herds them out of the restroom, causing a melee. As he shuttles her in, the guard orders her not to look at the graffiti spray-painted on the lavatory walls. “Can you read? These are things too dirty for women to read. Don’t read!”

Offside is a comical and joyous window into contemporary Iranian life. Its best quality is that Panahi avoids heavy-handed political lecturing, instead allowing the ludicrous situation to play itself out to make its points. His script is full of biting witticisms, especially from the tough-talking, chain-smoking soccer fan played by Shayesteh Irani, who feverishly debates the guards, tripping up their faulty reasoning for not permitting women to view the soccer match.

Panahi chose unknown actors to retain the film’s documentary feel. Shot on handheld video rather than film, Offside was made over a thirty-nine-day period, though many scenes were filmed during the actual game. This picture has an authentic atmosphere, mostly thanks to its street-smart dialogue, actual locations, and unobtrusive camerawork and editing. Despite uneven performances by some of the clearly-amateur actors, its characters seemed much more natural and believable than those played by professional A-list thespians in Sofia Coppola’s stilted entry in the cinéma-vérité genre, Lost In Translation.

Though its dialogue is mostly apolitical, Offside was banned by Iran’s censors. And though it has become a best-selling DVD on the Iranian black market, the film has yet to be shown there on the big screen. While Hollywood producers are quaking in their designer footwear at the prospect of revenge exacted against them, were they to portray the evil of Islamofascism, this little movie from inside the “Axis of Evil” gives cause for more than just hope. In Offside, we get to see the face of evil up-close and personal. And these days, evil is looking pretty bored. It just wants its discharge papers.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Comedies, Foreign Films, Independent Films, Movie Reviews |