300 (2006) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | March 16, 2007

Until Johnny comes marching home: Lena Headey and son send Gerard Butler to face the Persian army in the Battle of Thermopylae

Because Rough Men Stand Ready

[xrr rating=4.5/5]

300. Starring Gerard Butler, Lena Headey, Dominic West, David Wenham, Vincent Regan, Michael Fassbender, Tom Wisdom, Andrew Pleavin, Andrew Tiernan, Rodrigo Santoro, and Giovani Antonio Cimmino. Music by Tyler Bates. Cinematography by Larry Fong. Edited by William Hoy, A.C.E. Screenplay by Zack Snyder, Kurt Johnstad, and Michael B. Gordon, based on the graphic novel by Frank Miller and Lynn Varley. Directed by Zack Snyder. (Warner Bros./Legendary Pictures, 2007, Prints by Technicolor, 117 minutes. MPAA Rating: R.)

300—director Zack Snyder’s faithful, if controversial, adaptation of Frank Miller’s graphic novel—is a visually striking, though loosely interpreted, telling of the now-immortal Battle of Thermopylae.

Over a three-day period in 480 BC, King Leonidas and his three hundred Spartan bodyguards—with the assistance of about seven hundred Thespians and few thousand volunteers from other Greek city-states—fought the massive armies (estimated in most ancient accounts to have exceeded one million) of Persian Emperor Xerxes I at the Pass of Thermopylae on the Gulf of Malis. Through martial skill, fearlessness, and sheer audacity, Leonidas and his warriors held off the Persians long enough for the Athenians to prepare their navy to defeat the Persians at the Battle of Salamis, and thus save Greece.

The Battle of Thermopylae is a timeless tale of valor and honor. It takes its place in history with other legendary military standoffs—such as the Battle of the Alamo in 1836, where a few hundred Texans held off the Mexican army for thirteen days, and the 1939 “Winter War,” the World War II battle in which Finnish forces repelled over one million Russian invaders. Why, then, would a cinematic retelling of this remarkable event of so long ago prompt argument and debate today?

Historical film epics are rarely contentious enterprises nowadays, precisely because they portray events long since past. The ones that do spark heated debate tend to have religious themes, such as The Passion of the Christ and The DaVinci Code. If there’s any blasphemy to be found in 300, it’s against oracles and deities long since relegated to the dustbin of piety. Certainly there was little controversy in 1962 when Miller’s original inspiration, director Rudolph Maté’s The 300 Spartans, was released. So what’s happened in the forty-five intervening years to make Snyder’s remake-of-sorts so controversial?

In a word: multiculturalism.

Just as in the days of the ancient Greeks, the theme of saving the civilized West from barbaric Asiatic hordes is made quite explicit in 300, and given voice by King Leonidas (Gerard Butler): “A new age has begun, an age of freedom. And all will know that three hundred Spartans gave their last breath to defend it . . .The world will know that free men stood against a tyrant, that few stood against many.”

But unlike the days of the ancient Greeks, it’s now verboten to suggest the superiority, let alone the preferability, of Western culture to any other—including, presumably, Persian culture. And therein lies the controversy over this film. As “civilized people,” we’re not supposed to like war, much less relish military victory or the enemy’s demise. Hell, we can’t even use the word “enemy” anymore to describethe enemy. These days, when Hollywood goes to war, our fighting men are represented—at best—by that ubiquitous fixture of modern cinema, the “reluctant warrior.”

In contrast, Leonidas’s Spartans are hardly reluctant: Born and bred since childhood to fight for their military city-state, they’re professional soldiers who revel in the sting of battle. Xerxes (Rodrigo Santoro) sends an officer to present an ultimatum to his vastly outnumbered foe: “Spartans, lay down your weapons!” Rather than accommodating the Persians (as, say, the British Navy did circa 2007 AD), Leonidas roars back: “Persians, come and get them!”

In all of battle lore, Thermopylae stands as the ultimate “David versus Goliath” confrontation of civilizations. To most people familiar with Italian Renaissance art, this legend conjures in their minds the great statues by Donatello and Michelangelo. Both are nude figures of the young Hebrew warrior. Donatello’s David is but a boy. Without a care in the world, he leans on his sword with one hand, his other hand resting effeminately against his hip. Think of the eternally boyish Leonardo DiCaprio or Elijah Wood. More famous is Michelangelo’s manlier David. He’s muscular and stands erect, gazing off in serene contemplation. But, while Michelangelo captures David’s physical beauty and agility, his is a static, motionless fighter; the sculpture merely hints at the decisive moment ahead. Think Brad Pitt in Troy.

Any David who would have a chance of felling the monstrous Philistine had better be credible—one tough son of a bitch. Baroque-era sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini depicts just that kind of David—not naked, but clothed in soldier’s tunic, coiled back to fling the rock at Goliath. Bernini freezes his hero in motion: Taut, fierce, and grimacing, Bernini’s magnificent figure conveys both the intent and the execution of his bold, violent act.

The genius of 300 lies in Snyder’s and cinematographer Larry Fong’s ability to dramatize that same highly stylized sense of kinetic energy and unfreeze it. In particular, as Leonidas, the burly, bearded Scottish actor Gerard Butler is Bernini’s David brought to life.

Many reviewers have touted 300’s “comic book” visual sensibility. To me, it doesn’t look like a comic book at all, but rather like an oil painting set in motion. In fact, anyone familiar with Frank Miller’s striking illustrations will note the same qualities in those works. Using a color scheme of burnished tones, 300 manifests a sophisticated visual unity that owes much more to Jacques-Louis David’s painting The Oath of the Horatii (1785) and Akira Kurosawa’s film Ran (1985) than it does to Spider-Man orThe Fantastic Four. The rich, gorgeous Technicolor prints further intensify the viewing experience.

This visual stylization is one reason why 300 seems more real than the more historically accurate The 300 Spartans—even though the original was shot on location in Greece, while Snyder filmed his entirely on soundstages in Quebec. For example, the new, stylized Spartan is divested of his breastplate in favor of a uniform that makes him look like a cross between Kirk Douglas in his Spartacus get-up and wrestler Hulk Hogan in leather briefs. But the 1962 movie was filmed mostly from a distance, and the actors’ stiff performances were even more distant. The battle scenes looked like re-enactments; you could tell those Spartans were just a bunch of extras holding spears and shields.

Not so with this crew: While the scenery in 300 may have been rendered by CGI artists, the six-pack abs and bulging biceps on these Spartans are real, the product of a grueling five-month-long exercise regimen in which the actors also got Marine Corps “Hoorah!” attitude training. And instead of remote, set-piece battle scenes, Snyder gives us relentless, in-your-face combat—beautifully choreographed bloodletting. He conveys with blinding clarity how the Spartans could pull off such a sustained, concerted defense against a numerically superior force. When they go into their phalanx battle formation, you immediately realize why individual soldiers became such a deadly weapon when they fought in unison, something the 1962 film barely depicted.

I could tell 300 was going to be a smash hit when the intelligentsia descended upon this movie, unleashing all the sneering invective their vocabularies could muster—from “militaristic” and “fascistic” to “testosterone-laden” and “jingoistic.” Typical was Andrew Sarris, reigning “dean” of American film critics, writing in the New YorkObserver:

300 was as pathetically puerile as I had expected. Yet I can’t say that it wasn’t at least minimally entertaining. Indeed, there was a subtextual strangeness about the spectacle that would have made the ghost of Leni Riefenstahl nod in recognition.

Fortunately, the attempt to cut this superb picture down to size is more of an uphill battle than the one that Leonidas and his men fought. What repelled so many of ourliterati is also the source of its unexpected devotion among mainstream movie fans, (to the tune of $421 million in gross receipts, as of this writing): Miller and Snyder invest 300 with the stuff of mythical legend.

Butler’s Leonidas is a defiant figure with a bit of Phaeton and Sisyphus in him. He ignores the counsel of the Oracle (Kelly Craig), who orders him not to confront the Persians. “Trust the gods, Leonidas,” the governing council cautions him. Leonidas counters, “I would prefer you trust your reason.” Well aware that the very future of reason and democracy lies with his Spartans, the ascetic Leonidas faces down the decadent god-king Xerxes, proclaiming, “We wrest the world from your mysticism and tyranny!”

The epic tone of the story is further realized through the narration of Dilios (David Wenham), the one-eyed warrior who returns to Sparta to relate Leonidas’s story of courage and bravado to his own soldiers, firing them up to do battle again with the invading Persians. Mere days after his death, Leonidas is already elevated to the status of Epic Hero.

As Leonidas’s wife, Queen Gorgo, Lena Headey gives a stirring performance. When the movie opens, a Persian messenger (Peter Mensah) rebukes Leonidas: “Why does this woman think she can speak amongst men?” The queen fires back, “Because only Spartan women give birth to real men!” In a quiet scene before Leonidas heads off to war, she bolsters her king’s confidence: “Spartan: Come back with your shield—or on it.” It’s a lesson in honoring the spirit of a fallen loved one that’s completely lost on the Cindy Sheehans of our age.

History buffs and armchair philosophers have come out of the woodwork to chide viewers for buying into the movie’s inaccuracies. Just as common are complaints that the Greeks had slavery, that Sparta practiced infanticide, that the Spartan army was filled with conscripts, and that they—by gladly laying down their lives in a suicide mission—were hardly rational exemplars of individualism.

With all due respect to the Borg, however, resistance to 300 is futile. Its grand sweep and awesome storytelling had me cheering Leonidas’s fearless warriors. What can’t be denied is the movie’s premise that the seeds of individualism (which is a later, Enlightenment notion, anyhow) were planted in the Greek soil they so gallantly defended.

And, to anyone laboring under the misconception that soldiers are the opposite of individualists, I beg to differ. Over my years of military service, I’ve come to know many Airborne Rangers, Special Forces Green Berets, infantry grunts, Marines, and psychological operations specialists. To a man, these hardcore warriors personify the qualities of character exemplified by Leonidas and his hoplites: heads held high, rigorous discipline, physical prowess, intransigent certainty, moral courage, the ability to face reality at its most grim—and the willingness to think. When it comes to individualism, these guys walk the walk; everything else is just talk.

Through its images of crushing brutality, 300 reminds us that the bounties of civilization that we take for granted are a gift passed down through time from men like Leonidas. Or, in words famously attributed to George Orwell: “We sleep safe in our beds because rough men stand ready in the night to visit violence on those who would do us harm.”

With 300, Frank Miller and Zack Snyder have concocted an antidote to the steady diet of cynicism and derisive irony that Hollywood has been feeding our youth for decades. If you thirst for a tale that extols honor and reveres gallantry, in which the good guys are great and the bad guys are evil, then look no further than this stupendous cinematic achievement.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Action Movies, Dramas, Epic Movies, Graphic Novel Adaptations, Movie Reviews, War Movies |

Amazing Grace (2006) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | March 6, 2007

It was called "courtship" back then: Romola Garai goes straight to Ioan Gruffudd's heart by appealing to his reason

Grace Under Pressure

[xrr rating=4.5/5]

Amazing Grace. Starring Ioan Gruffudd, Romola Garai, Benedict Cumberbatch, Michael Gambon, Rufus Sewell, Youssou N’Dour, Ciarán Hinds, Toby Jones, Jeremy Swift, Nicholas Farrell, Sylvestra Le Touzel, Bill Paterson, and Albert Finney. Original music by David Arnold. Cinematography by Remi Adefarasin, B.S.C. Edited by Rick Shaine, A.C.E. Written by Steven Knight. Directed by Michael Apted. (Samuel Goldwyn Films/Bristol Bay Productions, 2006, Color, 111 minutes. MPAA Rating: PG).

Every decade or so, a motion picture comes along comes that so perfectly captures its subject’s heroic essence, that it becomes its subject. Such is the case with British director Michael Apted’s superb biopic on abolitionist William Wilberforce, portrayed passionately by Welsh actor Ioan Gruffudd.

Though Wilberforce is largely unknown to Americans today, this is an excellent introduction to the great English parliamentarian, who devoted twenty years of his life to eradicating the slave trade in Great Britain. A devoutly religious, though thoroughly skeptical man, Wilberforce figured prominently during both the Enlightenment and the Great Awakening.

As the movie opens, the viewer finds Wilberforce not at the beginning of his crusade to end the barbaric practice of slavery, but what seems its most hopeless point: Once one of the youngest members of the House of Commons, as the eighteen century draws to a close we find the once powerful orator gaunt and dejected, having nearly exhausted his fortune and health in service of his fight. We first see him riding in a carriage through the rain, as he happens upon a driver along the muddy road, whipping his fallen horse ceaselessly. Moved to the animal’s defense by mercy (he was a founding member of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals), Wilberforce nonetheless makes the driver cease his brutal flogging by using logical persuasion, informing him that the horse would more likely regain its strength if left to recover in peace for an hour. This simple exchange—achieving his ideals through practical means—reveals the key to Wilberforce’s forceful personality and unyielding integrity that would come to serve him so well throughout his career as a legislator.

He’s on his way to the resort town of Bath, where, he hopes, the famous mineral springs will heal his body, ravaged from bouts of colitis and suffering addiction to laudanum, an opiate prescribed by his doctors. When he arrives, however, his friends economist Henry Thornton (Nicholas Farrell) and his wife Marianne (Sylvestra Le Touzel) have a different sort of tonic in mind to cure what ails Wilberforce, as they slyly maneuver their friend into a “chance” meeting with a ravishingly beautiful young abolitionist and social reformer, Barbara Spooner (Romola Garrai). Resentful at his friends’ manipulations, he at first rebuffs her. Yet, the Thorntons are relentless and soon set him up again, later bringing Barbara to dinner at Wilberforce’s house.

Upon second meeting, however, their chemistry is too powerful to deny. Barbara and Wilber’s long conversation into the wee hours about his efforts in vain to stop the slave trade provides the vehicle for flashbacks, which comprise the majority of the story and dramatize Wilberforce’s tireless efforts as a younger man.

Elected to Parliament at twenty-one in 1780, Wilberforce barreled into the House of Commons full of piss and vinegar, taking on all comers with his confrontational debating style and razor-sharp wit. One dewy morning, however, an epiphany strikes him as he lolls about his lawn, transfixed in examining the intricacy of God’s handiwork in a spider web.

Caught up in his conversion experience, Wilberforce’s interest in the affairs of state evaporates as he’s about to devote himself to a life of religious contemplation. Yet, to those around Wilberforce—especially his friend in Parliament William Pitt the Younger (Benedict Cumberbatch, in a pointed, astute performance), angling to become the youngest Prime Minister of Britain at twenty-four—the divine spark firing within him would be better put to practical use. “Do you intend to use your beautiful voice to praise the Lord, or to change the world?” Pitt asks.

Wilberforce isn’t convinced until a group of Quaker abolitionists visit one evening, bringing along a liberated slave from the New World, Oloudaqh Equiano (Youssou N’Dour), whose memoirs about his horrific passage from Africa would soon spark public outrage against the peculiar institution. Seeing for the first time direct evidence of slavery’s evils, the brand on Equiano’s chest (“to let you know you no longer belong to God, but to a man,” the former slave explains) and iron shackles, Wilberforce gains new perspective when radical abolitionist Thomas Clarkson (Rufus Sewell) makes a rhetorical point. “We understand you’re having problems choosing whether to do the work of God, or the work of a political activist,” he says. Another guest (Georgie Glen) finishes the thought, “we humbly suggest that you can do both.”

Throwing himself into his task with all his vigor, Wilberforce floors a bill to abolish the slave trade every year—and every year the bill is defeated. Yet, he perseveres. In a nation where slavery is largely out of sight (thus, out of mind), Wilberforce constantly contrives ways to force it into the faces of “polite society.” He launches petition drives; he sponsors meetings for Equiano to lecture at and push copies of his book; at one gathering of the well heeled aboard a tour boat, the captain weighs anchor alongside a slave ship. Noting only one-third of the original 600 passengers survived the journey from Africa to Jamaica, Wilberforce exclaims to the MPs and their wives, “That smell is the smell of death. Slow, painful death….Breathe it deeply. Take those handkerchiefs away from your noses! There now, remember that smell.”

As his confession to Barbara ends, Wilberforce speaks as though his efforts lay buried in the distant past. Yet, while he seems too taxed to go on, Barbara finds only inspiration in his struggle. As morning breaks, the two announce their engagement to their friends. I like this little touch, seemingly coming out of left field: Without a word spoken between them of love (not to mention sex), their romance is subtly implied. While the two passionately talk of their ideals, sexual tension silently builds between them. This is old-fashioned moviemaking at its best: If Barbara’s fiery red tresses, flawless peaches and cream complexion and corseted, heaving cleavage weren’t sufficient to bag the man, then I suspect nothing would have stirred him. Ironically, I found the courtship scenes more erotically charged than the crassly explicated graphic sex in most movies nowadays.

Their marriage and Barbara’s pregnancy is a simple and beautiful metaphor for Wilberforce’s regeneration of health and will as he heads back to Parliament to fight the good fight once more. The movie’s political intrigue story really hits its stride here as Wilberforce, Pitt, Clarkson and Whig MP Charles Fox (Michael Gambon, best known for his role as Headmaster in the Harry Potter series) put their heads together to effect the end of the slave trade. This is the best I’ve seen in this genre since Otto Preminger’s political thriller Advise & Consent, based on Allen Drury’s novel.

The ending nearly left me breathless, witnessing Wilberforce’s ultimate triumph. The movie’s release was timed to coincide with the 200th anniversary of the slave trade’s abolition on February 23, 1807. Although Amazing Grace is a costume drama (which usually has me yawning), production designer Charles Wood’s painstakingly researched and designed sets give the movie an authentic feel, while Remi Adefarasin’s factual cinematography downplays idiosyncratic camera angles in favor of letting the actors and the settings predominate. Writer Steven Knight and director Apted’s deft balance of gravitas and levity gives the whole business a timeless feel befitting its hero’s magnitude, but without clumsy signposting.

The only drawback, I felt, was that veteran actor Albert Finney—in a bravura performance—seemed underused, considering his pivotal role as John Newton, the former captain of a slave ship who later repented, and penned the moving hymn for which the film is named. While the scenes depicting his influence on Wilberforce were succinct and heartrending, they also felt somewhat truncated.

Nonetheless, Amazing Grace has been well received by faithful and secular, conservative and liberal, alike. Still, it has generated some criticism on the pages of the Wall Street Journal, where guest columnist Charlotte Allen finds only a “cover-up” of Wilberforce’s fundamentalist brand of nascent Methodist Christianity. This is another entry in the Opinion Journal’s cloying series of “debunking” reviews by people who might be subject-matter experts, but haven’t the foggiest idea about what it takes to make an entertaining flick. I think she’s missing the forest for the trees: The slave trade abolition was Wilberforce’s apotheosis, which is exactly what Apted put up on the screen.

In a recent interview, that’s how producer Patricia Heaton (no stranger to religious conservatism she, an outspoken Pro-Life advocate) described Amazing Grace, as an inspiring biography of “the Abraham Lincoln of England,” and an antidote to our “age of such cynicism and despair, particularly about politics and religion.”

I agree: William Wilberforce is historically significant for his courageous actions in stopping an inhuman evil. While religion played no small part in motivating those actions, I really doubt so many talented people would’ve assembled such an unabashed labor of love as this movie had Wilberforce decided to spend his days contemplating God’s grandeur, while ignoring his own potential for greatness.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Biopics, Costume Dramas, Dramas, Independent Films, Movie Reviews, Political Dramas |

Becket (1964) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | February 24, 2007

Bosom buddies: Peter O'Toole and Richard Burton galavant together in the lavish "Becket"

Dictum Meum Pactum

[xrr rating=4.5/5]

Becket. Starring Richard Burton, Peter O’Toole, John Gielgud, Donald Wolfit, Martita Hunt, Pamela Brown, Siân Phillips, Felix Aylmer, Gino Servi, and Paolo Stoppa. Music by Laurence Rosenthal. Cinematography by Geoffrey Unsworth, B.S.C. Edited by Anne V. Coates, A.C.E. Screenplay by Edward Anhalt, based on the play by Jean Anouilh. Directed by Peter Glenville. (A Paramount Release of a Hal Wallis Production, 1964. Re-released by MPI Media Group/Slowhand Cinema Releasing, 2007. Color, 148 minutes. MPAA Rating: Not Rated.)

Say what you want about Martin Scorsese, auteur of the dark anti-hero aesthetic: The man’s clearly in love with Hollywood’s Golden Age. He’s put himself on the line almost two decades helming the Film Foundation, bringing public attention to the need for film preservation. Without their efforts, such masterworks as Lawrence of Arabia, How Green Was My Valley, On the Waterfront and Rear Window might have been lost to movie audiences forever. Now, thanks to them and Academy Film Archive director Michael Pogorzelski’s painstaking restoration, the 1964 Romantic classic Becket has been re-released in all its pomp, pageantry, and Technicolor glory.

Fresh off his brilliant turn in Lawrence of Arabia, Peter O’Toole gives a bombastic, explosive performance as hated Norman King of England, Henry II. Legendary Welsh actor Richard Burton plays his enforcer, Thomas à Becket, with cool-headed erudition in one of his finest screen roles.

Whether looting among the Saxons, taking liberties with wenches, or even having his wife taken from him by Henry, Becket’s a loyal pal and reliable stooge. Then, one day, trying to pull one over on the pesky clergy, Henry devises a brilliant scheme to install his drinking buddy as Archbishop of Canterbury.

But what begins as a fun romp in the “buddy picture” tradition, the movie veers into the sublime when Becket begins to understand the enormous gravity and honor required by his office. Transformed from yes-man into his own man, he refuses to render the things Holy before God to O’Toole’s spoiled brat of a Caesar, driven to betray Becket by an unrequited love that dare not speaketh its name.

A fascinating study of integrity in the face of corruption, Becket is an unforgettable Medieval epic from the same decade that gave us A Man for All Seasons and The Lion in Winter (also starring O’Toole). Experience the grandeur of a bygone era when “over the top” meant “larger than life.”

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Buddy Movies, Classic Movies, Costume Dramas, Dramas, Movie Reviews, Religious Dramas |

The Astronaut Farmer (2006) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | February 24, 2007

Come fly with me, come fly, let's fly away: Billy Bob Thornton has stratospheric dreams in "The Astronaut Farmer"

Barn Burner

[xrr rating=3.5/5]

The Astronaut Farmer. Starring Billy Bob Thornton, Virginia Madsen, Max Thieriot, Jasper Polish, Bruce Dern, Mark Polish, Jon Gries, Tim Blake Nelson, and J.K. Simmons. Music by Stuart Matthewman. Cinematography by M. David Mullen, A.S.C. Edited by James Haygood, A.C.E. Written by Mark Polish and Michael Polish. Directed by Michael Polish. (Warner Bros., 2007, Color, 104 minutes. MPAA Rating: PG)

A man wearing a spacesuit rides horseback across the sand dunes of a barren desert. He moves right-to-left, which spells trouble in movies’ silent language. There, he finds a calf that has strayed from its mother, lying in the sand. With a firm but gentle hand, he returns the lost beast to the herd.

It’s a scene whose incongruous visual elements reminded me of the 1968 sci-fi thriller Planet of the Apes. But this isn’t some spaceman marooned in a strange place; it’s the movie’s earthbound hero, a Texan named Charles Farmer (Billy Bob Thornton). A graduate of the University of Texas aerospace engineering program and one-time member of NASA’s astronaut program, Charlie left the space agency decades ago to run the family ranch after his father’s untimely death. Yet, through all the years of operating the ranch and raising his own family, he hasn’t let go of his dream of defying gravity.

In his barn, Charlie works obsessively, day and night, to build a rocket that may help him realize his dream. He models it after 1950s-era Atlas missiles, using salvage parts he buys on the cheap from rocket graveyards. His supportive wife, Audie (Virginia Madsen, enjoying a rewarding second wind onscreen), and their three kids get caught up in the daily up-and-down drama of his quest; indeed, his first-born, son Shepard (Max Thieriot), was named in honor of the first American in space, Alan Shepard.

However, their neighbors in the farm community regard Charlie as the town oddball, a frustrated man going through a bizarre mid-life crisis. There’s even an ongoing bet among the locals as to whether he “will ever go up, or blow up.” When he attends show-and-tell at his daughter’s elementary school in his spacesuit, her teacher humors him: to spur the kids’ imaginations, “we need more parents willing to dress up.” Foremost among Charlie’s woes: to finance his idea, he’s gone into hock for over a half-million dollars to the local bank, and they’re about to foreclose on his ranch for delinquent payments.

What I like about Thornton’s portrayal is that it actually justifies the townsfolk in pigeonholing him as a square peg. A quixotic figure with a bit of a mean streak (when he receives a foreclosure letter, he throws a brick through the banker’s plate-glass window), he reminds me a little of Anthony Hopkins’s quirky Burt Munro in The World’s Fastest Indian. But, when push comes to shove, Thornton recalls Burt Lancaster in so many of his tough-guy Western roles.

When Charlie forwards his flight plan to the FAA in anticipation of his expected launch, government officials dismiss him as a crank. But when he attempts to purchase high-grade liquid rocket fuel, he opens a can of alphabet soup: the FBI, CIA, FAA, NASA, and a host of other agencies descend upon his ranch to stop him. Even the local Child Protective Services closes in when Charlie decides to home-school his kids and draft them into his “space program.” In typical bureaucratic fashion, the CPS agent diagnoses the children, long-distance, as “brainwashed and violated,” and threatens his wife: “It’s about time you take charge of your family before someone else does it for you.”

A visit to his lawyer makes Charlie more aware of the pressure the government intends to apply. “With the Patriot Act,” the attorney tells him, “they can do whatever they want if they think it’s a threat to homeland security.” He advises Charlie to “embrace the media, invite them in for your protection.” Next, an astronaut from the old days (Bruce Willis, in an uncredited cameo) shows up to try to talk his eccentric friend out of his scheme. “They don’t let civilians into outer space, they let astronauts into outer space,” he says. We then learn that he’s been sent at NASA’s behest, because if successful, Charlie’s shoestring-budget launch could embarrass the space agency, which needs to defend its multi-billion-dollar budgets.

Eventually, Charlie defends himself before a meeting of federal officials in words that express the aspirations of the lone creator against the regulatory state and the pessimistic mindset:

It’s not your right to tell me whether or not I can launch into space…. I know we have laws; we’ve got all kind of laws. We’ve got more laws that tell us what we can’t do than anything else…. You see, when I was a kid they used to tell me that I could be anything I wanted to be. No matter what. And, maybe I am insane, I don’t know, but I still believe that. I believe with all my heart. Somewhere along the line, we stopped believing that we could do anything, and if we don’t have our dreams, we have nothing.

Soon after, in a fit of desperation, he launches his rocket, using an unstable kerosene-based fuel mix. It leads to disastrous consequences, but…

Well, I don’t want to give away the ending. Let’s just say that The Astronaut Farmer isn’t just a “feel-good movie”; it’s a preposterously “feel-good movie.” Its plot has to be taken with a grain of salt, but then, so does movie popcorn. I don’t go to the movies to bask in the mundane or to nitpick at continuity errors; I go to be entertained, perhaps even enlightened. And the Polish brothers tell a highly entertaining and sometimes thought-provoking tall tale.

In a way, I found The Astronaut Farmer to be one of those unbelievable flicks that you can truly believe in, because its creators take the preposterous seriously. That, and an expertly suspenseful buildup, makes all the difference. Somehow, they were able to take the plot of the forgotten Andy Griffith 1979 TV movie Salvage One, seize the theme of Francis Ford Coppola’s Tucker: The Man and His Dream, mix in cinematic references to John Ford Westerns and Apollo 13, and yet make it all jell. The movie’s only real drawback is an undistinguished soundtrack.

Credible acting enhances the story’s credibility. Billy Bob Thornton brings to the role of Charlie his quiet, idiosyncratic, yet steadfast demeanor. For her part, Virginia Madsen exudes a natural warmth and unflagging conviction. The supporting actors are well-cast, too, including sisters Jasper and Logan Polish as Charlie and Audie’s daughters; Bruce Dern as Audie’s cantankerous, aging father; and J.K. Simmons as the gruff FAA official who keeps setting up bureaucratic roadblocks in Charlie’s path.

What I most enjoyed, however, is that The Astronaut Farmer is a great family movie, as entertaining for the kids as it is for their parents. One of my earliest childhood memories is from late one night in July 1969, when I was four years old. My father woke me up and took me to the living room television set to watch Neil Armstrong walk on the moon. Lately, I’ve been thinking that perhaps I’ll never get to share a moment like that with my own son, who will soon turn two—that in his lifetime, man may never again set foot on the moon, let alone walk on Mars.

After watching Billy Bob Thornton’s unwavering, “can-do” performance for almost two hours, however, those dim prospects somehow seem to grow a little brighter.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Dramas, Fantasy Movies, Movie Reviews, Sci-Fi Movies |

The Lives of Others (2006) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | February 16, 2007

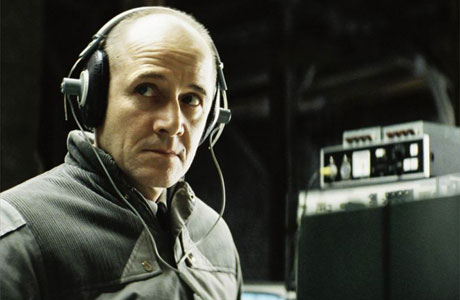

Ulrich Mühe, as Stasi agent Wiesler, is the ear in the wall, listening to your most intimate whispers

The Man in the Gray Flannel Life

[xrr rating=5/5]

The Lives of Others (Das Leben der Anderen). Starring Martina Gedeck, Ulrich Mühe, Sebastian Koch, Ulrich Tukur, Thomas Thieme, Hans-Uwe Bauer, Volkmar Kleinert, Matthias Brenner, Charly Hübner, and Marie Gruber. Music by Stéphane Moucha and Gabriel Yared. Cinematography by Hagen Bogdanski, B.V.K. Edited by Patricia Rommel, B.F.S. Written and directed by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck. (Sony Pictures Classics/Buena Vista International [Germany] GmbH, 2006, Color, 137 minutes, in German with subtitles. MPAA Rating: R.)

Earlier this year, I wrote: “I offer Pan’s Labyrinth as exhibit ‘A’ that the independent revolution is over.” After seeing the captivating Cold War espionage movie The Lives of Others from German writer and director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, I realize I may have spoken prematurely. Let me now humbly (but gladly) eat those words.

Made on a shoestring budget of $2 million, The Lives of Others is the most suspenseful psychological thriller I’ve seen in a long time, ranking with Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation or John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate. What’s more, it presents one of the strongest pro-individual, anti-collectivist themes of any movie I’ve ever seen—all the more surprising because it hails from, of all places, Germany.

Its key lies in its title, which seems at first glance drippingly altruistic. The year, appropriately, is 1984, and Hauptmann Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Mühe), is in his twentieth year as an agent of East Germany’s dreaded Ministry for State Security, commonly known as “Stasi.” The “shield and sword” of the Socialist Unity Party, 100,000 Stasi agents and 200,000 paid informers hold the small Soviet satellite nation in a death grip, monitoring and controlling the lives of its 17 million citizens.

Captain Wiesler is a meticulous interrogator, ruthlessly wearing down suspects until they confess. An instructor at the Stasi academy, he trains future agents always to be on guard. “The best way to establish guilt or innocence is non-stop interrogation,” he instructs his students. “The enemies of the state are arrogant. Remember that. ”

A humorlessly menacing man, Wiesler leads a lonely, Spartan existence in an antiseptic, sparsely furnished apartment in a concrete high-rise that houses many fellow agents. One day at the academy, his former classmate and current boss, gregarious Oberstlieutnant Grubitz (Ulrich Tukur), drops in with an assignment right up Wiesler’s alley. One of their artists appears to be straying from the flock, and Wiesler has been assigned to watch him. However, the subject in question is no dissident, but the most celebrated playwright in the DDR, Georg Dreymann (Sebastian Koch)—a citizen so loyal to the Party that he believes his is “the greatest country on earth.”

Later that evening, spying from a balcony seat with opera glasses, Wiesler detects the mark of subversiveness on Dreymann’s face as he watches the actors onstage performing his play. As Georg beams with proprietary approval, rising to applaud, Wiesler quietly utters to himself a one-word indictment that seals the dramatist’s fate: “Arrogant.”

Georg lives with longtime companion Christa-Maria Sieland (Martina Gedeck)—a radiant brunette who is as celebrated an actress as Georg is a writer (and to whom Wiesler clearly takes a fancy). While they are out of their flat, Wiesler’s technical team descends upon their home, bugging the place. “Operation Lazlo” is now in full swing, and Wiesler and his partner monitor their subjects around the clock from the apartment building’s empty attic.

At first, the surveillance of Georg and Christa appears fruitless. At a dinner party they host, a hysterical theatrical colleague (Hans-Uwe Bauer), who’s suffered detention and psychological torture at Berlin’s infamous Hohenschönhausen prison, accuses another director of being a Stasi informer. Georg is quick to defend his friend against the accusation.

Yet, through the course of his work, Wiesler makes some rather ugly discoveries about the investigation. He learns that it was ordered at the behest of national Culture Minister Bruno Hempf (Thomas Thieme), a porcine bureaucrat who’s extorted sexual favors from Christa under the threat of blacklisting her. Wiesler also eventually finds his friend Grubitz’s schmoozing to be a cover for vicious social climbing and discovers that Grubitz is complicit with Hempf’s scheme to use Stasi as a cat’s paw to eliminate Georg, his romantic rival.

Within Wiesler stirs a realization previously kept repressed: that his unquestioning faith in his country has enabled not his ideal of the perfect socialist state, but the hideous arrogance of avaricious thugs who run everything in the “workers’ utopia.”

Where once was the heel-clicking impersonality of a robot a conscience begins to grow. Wiesler comes to view Georg and Christa and their circle of Bohemian friends not as specimens under a microscope, but as real individuals, with hopes and dreams, loves and heartbreaks. Having grown a conscience, he soon also yearns for a heart, as he silently assesses the utter emptiness of his own life.

Swept up in his subjects’ personal lives, Wiesler’s detached spying turns into voyeurism. But it isn’t a perverted voyeurism, because, for the first time, the lonely captain catches a glimpse into a world of beauty, poetry, and music so alien to his two-dimensional existence. Sympathetic to the predicament of these enemies of the state, Wiesler begins covering for them, faking his reports, and remaining silent about Georg’s gradual disillusionment with the DDR after an old director friend (Volkmar Kleinert) commits suicide.

He overhears an argument in which Georg confronts Christa with knowledge of her affair with Hempf. Christa—already insecure about her talent—explains that she fears being blacklisted if she breaks it off. Wiesler feels compelled to protect her: He accidentally-on-purpose runs into her in a bar, pretending to be a fan, and tells her that her performances have inspired him. “Many people love you for who you are,” he says, sincerely. “You are even more yourself onstage than you are in real life.”

Christa dismisses his compliment, telling Wiesler he can’t really know her. “Did you know that I would sell myself for art?” she asks. “But you already have art,” he counters. “That would be a bad deal; you’re a great artist.”

Though his simple compassion, he gives Christa the strength to believe in herself and renounce her extorted affair with Hempf. But in doing so, Wiesler unintentionally sets into motion a nail-biting series of events that leads inexorably both to tragedy and redemption.

The Lives of Others is a superb film, top-drawer in every regard. Cathartic and ennobling, it recalls Fahrenheit 451 and We the Living in its presentation of tragic heroes forced to examine their deepest-held yet deeply mistaken principles. Hagen Bogdanski’s cinematography is compelling; through subtle differences in lighting he gives Silke Buhr’s sets an additional dimension that places the characters in emotional context. Shot with tungsten-balanced film, Georg and Christa’s incandescently-lit apartment radiates warmth; yet by capturing the omnipresent, fluorescent-lit settings of the Stasi world with daylight film, Bogdanski renders it cold and bloodless. Gabriel Yared’s simple, haunting soundtrack is the perfect evocative counterpart for the action onscreen.

The acting is realistic, but never naturalistic. Martina Gedeck is a pleasure to watch, not merely because of her physical beauty, but for her impressive emotional range. Ulrich Tukur’s capacity to turn on a dime from regular guy to cold-blooded manipulator is simply scary. And Sebastian Koch combines a physically imposing presence with a gentle, almost fatherly manner, reminding me of a younger Rutger Hauer.

But Ulrich Mühe steals the show as Wiesler. I have never seen an actor convey such a broad range of feelings within such narrow parameters. Where a Pacino or a Steiger would explode with ferocity, Mühe underplays, moving the audience with the sudden shift of an eyebrow, the drawing-in of a cheek muscle, or the quiet fall of a teardrop that betrays his sphinx-like façade.

Mühe began his acting career in communist East Germany. When government records were opened to the public after German reunification, he learned that his actress wife had been informing on him to the Stasi during the entire six years of their marriage. Clearly, he drew upon this reservoir of traumatic betrayal for this role.

The Lives of Others is flawlessly crafted, completely engaging the heart and mind. Most impressive is the fact that it’s Henckel von Donnersmarck’s feature film debut, released while he was still at the relatively young age of 32. In a recent interview, Henckel von Donnersmarck—who saw life behind the Iron Curtain first-hand when he visited family in the DDR as a child—spelled out his thoughts on communist repression as well as independent filmmaking:

The [phrase] “Independent film” makes sense to me only if it means that the director has full artistic control. How could a film be independent otherwise? … I know that very well from East Germany: Until the Wall came down, the Dictatorship of the Proletariat had Final Cut on everything: novels, plays, films, even paintings. Make no mistake: hardly ever did they actually censor anything. But looking back at the art of those four decades, you can still feel the state in everything, and most of the art of that era is very impersonal and boring. Because the artists censored themselves, often without knowing it.

Imagine my surprise, then, when the PC crowd at the recent Academy Awards ceremony—who feted environmental scam-artist Al Gore for his global warming crock-umentary—also bestowed the Best Foreign Language Film award upon The Lives of Others, rather than upon heavily favored Pan’s Labyrinth. (I think it deserved the nod for Best Motion Picture overall, but I’m not unhappy that the Academy gave that award to director Martin Scorsese’s The Departed, a consolation prize for snubbing him so many years).

This cinematic masterpiece is a cause for celebration. Rarely has a filmmaker burst on the scene in such total command of his material. The Lives of Others belongs in the same company as Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. I can only hope that Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck still has a Touch of Evil yet to come.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Dramas, Foreign Films, Independent Films, Movie Reviews, Political Dramas, Suspense Movies |