V for Vendetta (2006) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | March 24, 2006

Hugo Weaving is Snidely Whiplash on a mission in "'V' for Vendetta"

V for Vapid

[xrr rating=2/5]

V for Vendetta. Starring Natalie Portman, Hugo Weaving, Stephen Rea, Stephen Fry, and John Hurt. Screenplay by Andy Wachowski and Larry Wachowski. Directed by James McTeigue. Warner Bros., 2005, Color, 132 min. MPAA Rating: R.

V for Vendetta, the latest installment of the Wachowski brothers’s downward slide into formulaic banality. Directed by James McTeigue, the veteran first assistant director of such fare as Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones and the Matrix trilogy, V is his first directing effort in which nobody but himself can be blamed for monumental ineptness.

Upon its release, V for Vendetta sparked a lot of debate among libertarians for its anarchistic and nihilistic themes, and from that vantage point I was prepared to write this review. Easier said than done. After viewing nearly all four hours of this CGI special effects extravaganza (during which, inexplicably, the hands on my watch moved only two hours and twelve minutes), I scarcely found any dialogue coherent enough to be debated.

Set in the England of the future, V for Vendetta centers around its “hero,” V, played by Hugo Weaving. V is a refined man of culture (after all, who doesn’t enjoy hearing Julie London sing “Cry Me a River”?), who surrounds himself with now-banned books. For you see, the great Fortress has been taken over by “Norsefire,” a fascist theocracy. Its leader, Chancellor Adam Sutler, is a neo-conservative turned Big Brother, played by John Hurt. Just so the subtle novelty of a fuming and spitting despot who governs by Jumbotron isn’t lost on the viewer, the makeup people made certain to give Hurt a shortish-cropped mustache and a slicked-back shock of hair reminiscent of a certain Austrian corporal we all know and love.

Against this repressive backdrop, V nurses a four-hundred-year-old chip on his shoulder about the hanging of Guy Fawkes, who in 1605 tried to blow up the British Parliament. V also has a laundry list of personal grudges: he survived a secret government biological warfare experiment gone awry, as well as burns over one hundred percent of his body.

All of this is meant to guarantee the viewer’s sympathy for V’s sociopathic killing spree as a knife-wielding assassin and mad bomber. After curfew, he prowls London’s streets, avenging Norsefire’s innocent victims. He hides behind a plaster Guy Fawkes mask, which appears rather stiff, though not as stiff as Weaving’s acting.

V happens upon our damsel-in-distress, Evey Hammond, played by the waifish Natalie Portman, whom he rescues from a back-alley rape at the hands of the curfew police, in a deftly-choreographed, computer-generated bloodletting by stainless-steel daggers that produce the requisite “swoosh” and “chunk” sound effects. V sure moves pretty fast and furious for someone who’s suffered one-hundred-percent body burns. According to the actuarial tables, he shouldn’t be moving at all; but that’s a moot point.

After dispensing with the goon squad, V introduces himself to Evey by way of an alliterative soliloquy containing forty-seven words beginning with the letter “V.” It’s meant to be charming and chivalrous, but comes off more like Snidely Whiplash doing a Jesse Jackson impression. V then asks Evey to accompany him for a night on the town, whereupon he blows up that citadel of British jurisprudence, the Old Bailey. Talk about fireworks on a first date!

The next day, the government takes credit for his dynamiting job, claiming that Old Bailey was condemned as unsafe. Unfortunately, another side effect that V suffered in prison was an abiding and strident narcissism; so he takes over television broadcast studios to inform Londoners that he blew up Old Bailey, and that in one year—on the day Guy Fawkes burns in effigy—he will level Parliament. Through another subtle plot twist—Evey just happens to work as a gofer at the TV studio (surprise!)—V manages to sweep her up as his innocent accomplice. This sets up the tedium that follows, right up to the anticipated anticlimactic climax.

V for Vendetta doesn’t just rip off George Orwell’s 1984; that would imply some sort of thematic unity. Rather, this schizophrenic action pic is a pastiche of at least a dozen works far greater than itself. When not squiring Evey about his secret lair a láThe Phantom of the Opera, V hunts down the bastards responsible for his fate in pale homage to The Count of Monte Cristo, while inciting the people to take back their country in a side plot embarrassingly reminiscent of that other “V”—the 1983 TV mini-series about invading aliens from outer space. The film snitches from cinematic styles and genres, too. There’s even a flashback that seamlessly melds the innocence of awakening lesbian passion with lush Merchant-Ivory “Room With a View” cinematography.

Amidst all the slow-mo slicing and dicing, V is fond of chiding his deserving prey that “ideas do matter.” In his televised appeal to the people, he lays the blame for their loss of liberty where it properly belongs, at their own feet. The film’s tagline—“People should not be afraid of their governments; governments should be afraid of their people”—is a rather Jeffersonian conception that rings with the spirit of limited government.

Yet for all its nods to individual liberty, V for Vendetta fetishizes freedom through its direct advocacy of anarchy. Justifying his annihilation of Parliament, V argues that “the world doesn’t need a building, it needs an idea”—patently ignoring the ideas of common law and representative democracy that very building embodies. Thus we are brought to V’s conclusion: By destroying the betrayed institutions of democracy, somehow, the people will regain their freedom.

This is an obscenity to anyone who remembers his World War II history. From Parliament’s halls, Winston Churchill rallied Britons in their “finest hour” to face down Hitler’s Third Reich on the eve of the Battle of Britain. In their sick revision, however, the Wachowskis defeat the Nazis by leveling Parliament—never mind the fact that the Nazis burned down the Germans’ Reichstag to consolidate power.

Despite V’s pompously vague appeals to the power of ideas, all that viewers are left with is a lot of the moral relativity piffle that leftist professors are so fond of quoting, to the effect that “one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.” Substitute the World Trade Center and the Pentagon for Old Bailey and Parliament, and you’ll get the drift of this sickening allegory.

Or, to drive the point closer to home, substitute, in Parliament’s place, Columbine High School in suburban Denver. Before the murderous rage in which Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris massacred twelve schoolmates and a teacher, they produced an amateur video glorifying their school’s wanton and nihilistic destruction.

Thankfully, they took their own sorry lives immediately thereafter. Imagine what cinematic epics Klebold and Harris might have scripted from their prison cells. Their insane musings wouldn’t have looked much different from this nauseating waste of celluloid.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Action Movies, Dramas, Graphic Novel Adaptations, Movie Reviews |

The World’s Fastest Indian (2005) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | February 26, 2006

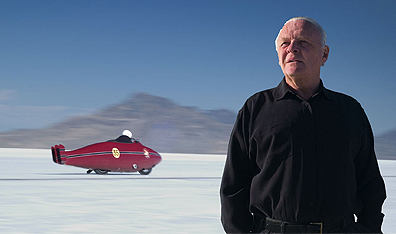

Anthony Hopkins as Burt Munro anticipates breaking the world land speed record at the Bonneville Salt Flats

Another Lion in Winter

[xrr rating=4.5/5]

The World’s Fastest Indian. Starring Anthony Hopkins, Diane Ladd, Paul Rodriguez, Aaron Murphy, Christopher Lawford, Annie Whittle, Chris Williams, Jessica Cauffiel, and Saginaw Grant. Written and Directed by Roger Donaldson. (Magnolia Pictures, 2005, Color, 127 minutes. MPAA Rating: PG-13.)

In this independently released sleeper, consummate actor’s actor Anthony Hopkins brings a deceptively diminutive, real-life hero—legendary motorcyclist Burt Munro—to the big screen in a larger-than-life biopic. Directed with heartfelt passion by Australian Roger Donaldson, The World’s Fastest Indian tells the improbable story of one man’s all-consuming mission to become the fastest man on two wheels.

For twenty-five years, New Zealander Burt Munro has dreamed of trekking far from the shores of his town of Invercargill to take a shot at breaking the motorcycle land speed record at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah. But as the movie opens, we find not some youth with the latest tricked-out bike, but a pensioner pushing seventy and nursing hardened arteries, for which he must take nitroglycerin pills to prevent his heart from giving out. Pushing his dream even farther from the reaches of reality, he plans to ride to glory on a mechanical antique—his beloved 1920 Indian Scout. The bike originally left the factory able to reach a top speed of fifty-four miles per hour; but Burt intends to reach 200.

Hopkins is brilliant in capturing the unassuming outer persona of Munro. His portrayal gives us the sense not that we are in the presence of greatness so much as resolute persistence. Burt Munro is a self-effacing charmer and tinkerer whose eccentric personality is out of phase with his stolid, suburbanite neighbors. They, understandably, are more than mildly annoyed by his loudly revving bike engine before the break of dawn, and by his absent-mindedness about getting around to mowing his lawn.

One neighbor, though, twelve-year-old Tom, sees in Burt not some tottering old crank, but a hero and mentor. The scenes in Burt’s tool shed as Tom listens to the old man’s reminisces and aspirations are among the movie’s most sincere and enchanting. Even as we are subtly prodded not to take Burt completely seriously, Tom’s uncorrupted awe and youthful idolization help stoke the man’s quiet inner passion to see his plan to fruition.

“If you don’t follow through on your dreams, you might as well be a vegetable,” he counsels the boy.

“What kind of vegetable?” Tom inquires.

With biting succinctness, Hopkins replies, “A cabbage.”

One thing that separates Burt from a legion of dreamers who abandon their ambitions is his resourcefulness. On a shoestring budget, he constantly employs his mechanical ingenuity to modify the Indian, with which he is more intimate than he is with any living person. Never taking a day off, not even for Christmas, he spends untold hours and days forging new pistons and souping up his “motorsicle,” readying it for the big trip.

Much of the movie concerns itself with Burt’s personal odyssey to Bonneville for “Speed Week.” He finances part of the journey by working as a cook and dishwasher on a freighter bound for America. Upon arrival, he works late into the night repairing a cheap old clunker to tow the Indian across the desert to Utah. Along the way we meet a benevolent, motley crew who happen into and out of Burt’s life, including a fast-talking used car salesman (comedian Paul Rodriguez) whom Burt nearly kills while test driving on the left side of the road; a hotel desk clerk in drag (Chris Williams); an aging American Indian (Saginaw Grant) who helps Burt out of a tight spot; a widow, Ada (Diane Ladd), who takes a respite from loneliness during a brief encounter with Burt; and an Airman on furlough from Vietnam (Patrick Flueger).

In a quietly reflective scene, Burt relates to Ada what motivates him to push himself further:

A man is like a blade of grass. He grows up in the spring, strong and healthy and green. And, then he reaches middle age and he ripens, as it were. And, in the autumn, he finishes, he fades away and never comes back…I think that when you’re dead, you’re dead.

In this soliloquy Hopkins summarizes the film’s philosophy—that there’s no room for soothing stagnation on Earth by nurturing dreams to be fulfilled only in the hereafter. Life must be lived now, because tomorrow may never come.

Arriving in Bonneville, Burt must overcome new challenges strewn in his path: Speed Week organizers inform him that he forgot to pre-register; his ancient motorcycle has no safety equipment; he’s simply too old to be allowed to race in the time trials. But because of his dogged refusal to back down after traveling around the world, the race organizers humor Burt and allow him to enter the time trials.

The World’s Fastest Indian is superb in every respect. For director Donaldson, it represents the fulfillment of a double obsession: dramatizing Burt Munro’s breathtaking pursuit of his lifelong goal, and realizing Donaldson’s own quarter-century quest to bring his hero-friend’s incredible story to the screen. David Gribble’s lush cinematography is full of vibrant hues and astounding moving camerawork, expertly capturing racing vehicles traveling at speeds topping 200 miles per hour.

But it’s Hopkins who ultimately makes this picture work so well, in his most heroic role since playing efficacious industrialist Charles Morse in 1997’s The Edge. Though not given to hyperbole, Hopkins proclaimed The World’s Fastest Indian “the best film I’ve been in.” I agree, absolutely. His natural, evocative portrayal of a man who refuses to resign himself to the tedium expected of one in old age will inspire viewers of all ages. His Burt Munro is not content merely to dream, but is that rare individual who makes his dreams reality. “For me, it’s a big change,” Hopkins commented about Munro, “because it’s a real winner of a guy. I’ve had a good career playing psychopaths or uptight people, and I’m fed up with those.”

Ironically, his rousing performance of this aging hero is the best depiction of the spirit of youth I’ve seen in a decade. Spend a couple hours with Burt Munro, and you’ll find in his quiet resolve the idealism you may have mislaid somewhere along the way.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Biopics, Dramas, Independent Films, Movie Reviews, Sports Movies |

Sideways (2004) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | November 25, 2004

Paul Giamatti and Virginia Madsen in Alexander Payne's "Sideways"

Bacchanalia

[xrr rating=4/5]

Sideways. Starring Paul Giamatti, Thomas Haden Church, Virginia Madsen, Sandra Oh, Marylousie Burke, Jessica Hecht, Missy Doty, M.C. Gainey, Alysia Reiner, Shake Toukhmanian, and Duke Moosekian. Cinematography by Phedon Papamichael, A.S.C. Edited by Kevin Tent, A.C.E. Music by Rolfe Kent. Screenplay by Alexander Payne and Jim Taylor. Based on the novel by Rex Pickett. Directed by Alexander Payne. (Fox Searchlight Pictures, 2005, Color, 126 minutes. MPAA Rating: R.)

As a rule I dislike most “independent” films, especially since that moniker has become a synonym for pathological dependence on Robert Redford. The main reason I avoid them is because so many are pretentious, full of affectation, forced dialogue, and self-conscious camerawork. Too many “serious” filmmakers these days still haven’t mentally left film school.

Fortunately, independent screenwriter/director Alexander Payne is not one of those. With Sideways, he and co-screenwriter Jim Taylor have crafted a genuinely funny, sad, and mad odyssey through California’s wine country.

Sideways follows a pair of mismatched buddies—has-been actor Jack (Thomas Haden Church) and his never-was novelist pal, Miles—on a romp during Jack’s last week of freedom before marrying up. Miles, played bittersweet and sour by gifted character actor Paul Giamatti, is a touchy bundle of overwrought nerves, unable to unwind from his depression even as he attempts to show Jack a good time. The two sojourn through vineyards around Solvang and Buellton in northern California, tasting wines and golfing, but Jack is much more interested in trying to nail any female that happens his way, and offers to get Miles laid.

The pair soon happens across a couple of sirens in the wine and hospitality business, waitress Maya (the ever-gorgeous and talented Virginia Madsen) and pourer Stephanie (Sandra Oh) and extroverted Jack sets the four up for a double date. It is interesting watching the two couples, how likes attract. Jack, who perpetually lives in his 1970s tropical shirts, immediately hits it off with born-to-be-wild Stephanie, and make like a couple of rabbits in no time. Love and lust, though, have not been as kind to Miles and Maya, who at first approach each other warily, tentatively. Their connection is less animal, more cerebral.

At first (despite Jack’s coaxing and pushing Maya onto him), Miles is hesitant to accept her, whom he off-handedly dismisses because she’s a waitress, but at Stephanie’s house, the two find they both indeed have a passion for fine wines.

There is a beautifully sublime scene, in which Giamatti and Madsen discuss their shared love of wines. The dialogue is economical and intelligent, yet sensually evocative: For through their ostensible conversations about pinot grapes and wine tasting, the viewer is given a glimpse into their souls. Their exchange is heartfelt, and is the most understated romantic scene I’ve experienced since Rex Harrison and Gene Tierney’s contemplation of the sea in The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947). For a brief moment, Miles and Maya have made a connection, which just as fleetingly dissipates. The moment is lost, yet Payne communicates visually in the next few shots that their connection still remains, that it indeed has cemented an implicit bond of understanding and affection between them.

Unfortunately, we learn that Stephanie has fallen for Jack, and fallen hard. At this point, the relationship between Miles and Jack changes as well: In the movie’s opening scenes, Jack was clearly in charge emotionally, a big brother warning Miles not to ruin their fun with his depressive bouts.

But as it becomes clear that Jack’s lustful behavior is opening Stephanie up for a lot of emotional pain, Miles emerges as the more mature of the two, trying to communicate to the slower-witted Jack that his devil-may-care attitude is amoral and potentially hurtful.

This is a great movie (and it tries to be a movie, not a film) which takes its characters—but never itself—seriously. The acting doesn’t even seem like acting, it’s so natural and unforced. Madsen is brilliant, and her delivery of the speech about how she came to have a passion for wine, how every bottle is breathing with life coursing through its veins, is direct (but in an subtle way) and makes a deep impact. Sandra Oh is sexy and sultry—I love her line, “I need to be spanked!” It has a Lauren Bacall quality to it. She’s just as equally convincing when she rages at Jack for leading her on. Church is perfectly cast as the California surfer-boy actor type who never grew up. Viewers will also recognize a pair of Payne regulars Phil Reeves (Election and About Schmidt) and M.C. Gainey who played biker vet Harlan in Citizen Ruth in the cast as well, the latter in a bizarre and hilarious scene in which Miles tries to retrieve Jack’s lost wallet.

But, this movie is Giamatti’s. I’ve admired his acting ever since I saw him as Howard Stern’s hyper and vengeful boss in Private Parts, and felt sorry for his pearls-before-swine performance in Duets, in which he and Andre Braugher were the only good things about that dreadfully bad movie.

In Sideways, Giamatti comes across as thoroughly believable. He manages to even infuse his manic episodes with a light comedic touch. He’s at times surly, at others serious, but never hackneyed. The scene that made the deepest impression was near the end of the movie, in which he meets his ex-wife, learning that she’s pregnant by her new trophy husband, appropriately named “Ken.” Watching him trying to keep a stiff upper lip was painful, because Miles is the kind who wears his heart on his sleeve. Yet, I was inwardly cheering for him, knowing the triumph of emotional control it was for him. There was never a trace of what David Mamet calls “Hollywood huff acting” about his performance—Giamatti never resorted to sighs, grunts, and groans to impart what his character was going through, but simply acted his way through it, convincingly and powerfully.

With Sideways, Alexander Payne has carved a niche for himself as the master of the cynical comedy. With this movie, along with Citizen Ruth, Election, and About Schmidt, he has swerved into being the next Billy Wilder. However, Payne has earned those laurels on his own, defining his genre through his own comedic and dramatic vision. He never apes Wilder, unlike the Coen Brothers, who’ve self-consciously fashioned themselves as Preston Sturges’s heirs.

One quality Payne’s movies have in common with Wilder’s is that their endings leave room for hope. Some deride these as typical Hollywood happy endings. Yet, Payne grants his protagonists a measure of redemption (except for eternal little man Jim McAllister in Election). Whether these endings are predictable or seen by some pessimists as sappy is not the point. I see it, rather, as sort of a confirmation that man’s lot in life is not misery. That misery—not happiness—ought to be the aberration is Payne’s message. Like Wilder, he is indeed a cynic. But, a cynic is just a frustrated idealist.

Sideways is in limited release, so I had to wait a month for it to come to San Antonio to see it. But, like a fine vintage bottle of wine, it was well worth the wait. It is indeed a movie to savor, again and again.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Buddy Movies, Comedies, Dramas, Independent Films, Movie Reviews |

Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | December 23, 2003

Frodo, you're nothing to me now. You're not a brother, you're not a friend. I don't want to know you or what you do. I don't want to see you at the mead hall, I don't want you near my castle. When you see our mother, I want to know a day in advance, so I won't be there. You understand?

Mediogre

[xrr rating=3/5]

Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. Starring Elijah Wood, Viggo Mortensen, Ian MacKellan, Sean Astin, Billy Boyd, Dominic Monaghan, Miranda Otto, Orlando Bloom, and Cate Blanchett. Music by Howard Shore. Cinematography by Andrew Lesnie. Production design by Grant Major. Costume design by Ngila Dickson and Richard Taylor. Edited by Jamie Selkirk. Screenplay by Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens, and Peter Jackson. Based on the novel by J.R.R. Tolkein. Directed by Peter Jackson. (New Line Cinema, 2003, Color, 201 minutes. MPAA Rating: PG-13.)

I did not seek out this movie, because I never could get into D&D costume flicks. I suppose that the closest I came to being a potential reveller in these movies is that I am a fan of Ronnie James Dio’s album “Killing the Dragon,” but that really is quite a stretch.

First of all, the cinematography is gorgeous: Lots of light streaming in nooks and crannies and crevices. A lot of muted tones of pewter, forest green and cobalt blue–it made me wonder why Peter Jackson didn’t have it filmed in black and white; would have made more sense, but most people have an irrational aversion to black and white, particularly those who are epic movie fans.

The costumes and sets were very good and very believeable, as were the special effects. Lots of Indiana Jones stuff, but without Indiana Jones.

Mostly, though, my chief complaint is with the script and the acting. I’m sure glad that Michael Medved was there on his “Movie Minutes” radio sidebar to tell me that this was about good and evil. I sort of gathered that from Elijah Wood running aroud everywhere toting this gold ring which has supernatural, but very unlucky powers. He really wants to get rid of it bad, sort of like a Medieval “Talking Tina” doll.

There’s only one way to totally get rid of it, though, and that’s why what otherwise would have been a half-hour “Twilight Zone” episode has been turned into a mini-series Renaissance faire that’s longer than Wagner’s (coincidentally) Ring cycle.

Actually, this plot would have been better as a “Star Trek” episode. After an hour of the ring causing Tribbles in the cargo hold and invading Klingons, Jim Kirk could have soliloquy’d:

“Got….to….get….rid…of…ring,” whereupon Spock would have replied, “Captain, the logical course of action is to send it back to the jeweler, and get a refund. It’s still under warranty.”

Although this collection of celluloid deals with nerds before the advent of daily bathing, I often wondered, “did this fellowship of crusaders get their perfect 21st century teeth because the ring comes with a comprehensive dental plan?”

The main weakness of this movie is the acting. Sure, Sir Lord Knight Ian MacKellen gives a believeable performance as the Old Guy in the Witch’s Hat. The rest of the movie, however, consists of a bunch of pretty fair haired lads and lasses who impart inscrutable piffle to each other in the form of deeply profound sounding monologues, delivered in a deeply anesthetizing monotone. Everything is so gosh darned deep and weighty, but when these folks lock their glassy Jim Jones Unification Church eyes, we in the audience are sure to know: “Ah ha! Here comes another clue! Now we can get out our Little Orphan Bilbo decoder rings to try and figure out just what in Hades they’re talking about!”

Now, this may be my fault. When I was in high school, I scoffed at the D&D playing, “Chronicles of Narnia” reading, Hobbit-obsessing nerds. I was a more socially well-adjusted nerd, belonging to the far more sensible backgammon club and into new wave music like Devo and Duran Duran. So, I can’t exactly relate to all this knights of the ringtable esoterica. So, if you’re inclined to be one who’s into this sort of thing, I’m sure it will have you on the edge of your seat, comparing the movie to the book.

But, for the unconverted, I really wish that the actors had been primed for these pictures by being forced to watch movies by Errol Flynn, Ronald Colman, Charlton Heston, and Orson Welles, to see how to breathe some life into their anemic performances. My God, it was as though the whole cast somnambulated their way through the script on Prozac. Heston wouldn’t have done it that way. Oh, no: He would have had a “damn it all to hell, you damn dirty apes are all made out of soylent green!” moment or two.

Orson Welles would have waddled through the enchanted forest, drawling in Southern dialect some about how the corrupt ring could be bribed, and the dashing Colman and Flynn would have swashbuckled away the dragons and flying monkeys from Wizard of Oz without even getting a run in their tights. But, that would have been seen in this sophisticated era as less profound and more entertaining. Entertaining don’t get Oscars nowadays.

I was dragged to watch this by a cousin who’s into all this sort of thing. When it was over, I informed him not to take me to the movies again and be forced to sit through an entire trilogy. When he told me I had only sat through but one installment of this burnished blather, I–unable to quite believe him–thanked him for not subjecting me to the other two.

My time is valuable, and I have more important things to do with it.

Such as sitting on my back porch and watching the grass grow.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Costume Dramas, Dramas, Epic Movies, Fantasy Movies, Movie Reviews, Sequels |

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | December 10, 2003

Eli Wallach and Clint Eastwood are the West's odd couple in "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly"

Fistful of Leone

[xrr rating=5/5]

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Starring Clint Eastwood, Eli Wallach, Lee Van Cleef, Aldo Giuffre, Luigi Pistilli, Rada Rassimov, Enzo Petito, Molino Rocho, and Mario Brega. Cinematography by Tonino Della Colli. Edited by Eugenio Alabiso and Nino Baragli. Restored version edited by Joe D’Augustine. Sets and costumes by Carlo Simi. Music by Ennio Morricone. Screenplay by Age-Scarpelli, Luciano Vincenzoni, and Sergio Leone. Directed by Sergio Leone. (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer/United Artists Pictures, 1967 [Restored 2003], Technicolor, 179 minutes. MPAA Rating: R.)

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is Sergio Leone’s magnum opus. An audacious undertaking, with a totally implausible plot and over-the-top acting, it would have flopped miserably in any other director’s hands. Only someone so committed to his artistic vision as Leone could have pulled off this bombastic pageantry of human nature in all its facets, its capacity for cynicism, greed, bloodlust, revenge, heroism, redemption and honor.

This movie must be experienced. I had seen the DVD of the truncated 1967 version countless times, but I had not seen it on the big screen until this gorgeous restoration I was privileged to watch at Manhattan’s Film Forum. The stereophonic soundtrack of Ennio Morricone’s score pummels you square in the chest from the moment the Lardani titles blast onto the screen in a blaze of Technicolor fury. The montage of color, interspersed by stark black and white visages of Eastwood, Van Cleef and Wallach is a tough act to follow, like Saul Bass’s iconic title sequences.

This MGM/UA print was first restored in Italian by Cineteca Nazionale. The English-language restoration was spearheaded by Martin Scorsese, whose efforts with the Film Preservation Foundation have helped fund preservation of America’s celluloid heritage. Both Eli Wallach and Clint Eastwood returned to the sound studio to dub new dialogue for approximately twenty minutes of restored footage. Both sound a little older and scratchier, but these added scenes help to explain both Tuco’s and Angel Eyes’ gangs and some plot points that were previously unclear. However, they both sound great! (The late Lee Van Cleef’s voice was dubbed by a professional voiceover artist, and actually sounds more on target than the two surviving leads). The movie now has the true feel of a sprawling epic, one that’s earned its right to take its time.

Even though the original was shot silent and then overdubbed in Italian, the English-language version packs the greatest punch, thanks to Mickey Knox, who wrote the English language dialogue. Knox crafted lines that lived up to the larger than life screenplay. You’d swear the original was in English, the dialogue is so perfectly tailored!

But the vision is singularly Leone’s. It starts slowly, as a band of bounty killers home in on their prey, small-time bandit Tuco Benedicto Pacifico Juan-Maria Ramirez (The Ugly, played by the venerable Eli Wallach). They pile through a saloon door, then the camera immediately pans away laterally. Suddenly, his body hurtling through the front window in a rain of glass, Tuco bursts onto the street—in what has to be the most absurd grand entrance in screen history—revolver in one hand, a chicken leg in the other. It’s total chutzpah on Leone’s and Wallach’s part.

If you think that can’t be topped, watch Wallach’s entire performance. Animated is putting it mildly. More than a performance, Wallach is a one-man band, nay, army. Never has such a selfish, petty, ratty and shifty little man been played so larger than life. Wallach smirks, scurries, grimaces, chuckles, shouts, bellows, and slyly oils his way across the screen in what has got to be the hammiest performance ever by a method actor. Or any actor, for that matter: He makes Orson Welles, Burt Lancaster and Charles Laughton look like the gray and sullen cast of an Ingmar Bergman snoozefest. Wallach is so alive with passion that he literally sweats his performance out through the filthy pores on his stubble-ridden face. And he’s wonderful!

If that’s a tough act to follow, you haven’t met The Bad. They don’t come any badder than Angel Eyes, Lee Van Cleef’s hired killer who’s got ice water running through his veins. Van Cleef is ruthless, bold and heartless. Riding out of nowhere onto a doomed man’s rancho, Angel Eyes pays a visit, carrying out a murder for hire. The price: $500. But the victim offers him $1000 to look the other way. No dice: Angel Eyes isn’t in it for the money. Rather, he’s a man who loves his work, and always sees the job through. So, the poor sod dies anyway.

Clint Eastwood is as cool as a cucumber as The Man With No Name (but really one with sort of a name, in this case “Blondie,” which is Wallach’s moniker for him). It’s fun watching the ongoing relationship between Blondie and Tuco as bounty hunter and prey. In another life, they would have been great pals, but in this life (“we’re all alone in this world,” Tuco confesses to Blondie, half seriously, half cynically) their love of money is thicker than friendship. So, they invent ingenious and cruel ways to exact revenge of each other.

It’s during one of Tuco’s sadistic plots—in which he marches pale-faced Eastwood across 100 miles of scorching desert—that the action finally comes to a head: A driverless stagecoach full of wounded Confederates happens across their path, and through a twist of fate, Tuco and Blondie each have two halves of a secret which (if put together) will make them a quarter million dollars richer. But without each other, the two halves are worthless. Thus does Tuco do a 180 from brutal executioner to Blondie’s would-be savior. Now that he could be rich, he suddenly realizes how valuable their friendship is.

It’s not before long that they wind up with Angel Eyes, as they’re captured by Union soldiers. At the prisoner of war camp, a deadly game of cat and mouse begins. Van Cleef is now more restrained and less thuggish as he deals with Tuco to extract the secret; his henchman Wallace (Mario Brega, a Leone stalwart), beats it out of Tuco.

In epic fashion, after a shootout in a deserted town and a bridge demolition that rages across the screen, Tuco, Blondie and Angel Eyes make their way to the cemetery where the treasure is buried. In a fanfare of brass, percussion and chorus, the three face each other down in the cemetery plaza. It’s a gorgeous and cathartic set piece. Credit must go not only to composer Ennio Morricone but also to musical director Bruno Nicolai, who conducts the score con fuoco.

Sergio Leone’s trilogy of Westerns with Eastwood, which began with Fistful of Dollars and For a Few Dollars More, were sneeringly called “Spaghetti Westerns” by skeptical movie reviews when first released. In the 1970s, film theory types renamed them as “revisionist.” But, see this on the big screen for the first time, thirty-seven years after it was shot, and there’s only one label that so perfectly adheres to Il Buono, Il Brutto, Il Cattivo:

“Masterpiece.”

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Action Movies, Black Comedies, Classic Movies, Comedies, Dramas, Foreign Films, Movie Reviews, Restored Re-releases, Sequels, War Movies, Westerns |